The Man in Room 1046

In 1935, a man with no luggage, using a fake name, was found tortured to death inside a locked room at the Hotel President in Kansas City. His last words were a lie, and the police had no weapon, no suspects, and no motive.

From a mysterious figure named "Don", to a potential link to a New York serial killer, we peel back the layers of the baffling case of Room 1046, a century-old mystery where each clue only leads to more questions.

Some stories linger in the dark corners of our history, whispering of secrets and tragedies that refuse to be forgotten. They haunt the places where they were born, etching themselves into the very fabric of a building, a city, a single solitary room. This is one of those stories. It's a story that begins with a name — a name that wasn't real — and ends with a question mark that has stretched across nearly a century. It's a story that asks us to look at a locked door, and wonder not only who is inside, but what terrible truths are locked in with them. This is the story of the man in Room 1046.

Kansas City, Missouri. January 1935.

To understand the mystery that would soon unfold, you have to understand the city itself. This was not just any American town. It was a kingdom, ruled by the infamous political boss Tom Pendergast. His political machine controlled everything, from the mayor's office to the police department. It was a city where the Jazz Age hadn't so much ended, as it had gone underground, thriving in the smoke-filled backrooms of speakeasies that had barely bothered to hide their existence, even before Prohibition's recent repeal. It was a city of stark contrasts, of Art Deco skyscrapers scraping the Midwestern sky, while down below thousands lined up at soup kitchens, the Great Depression having emptied out the pockets of the working man. It was a place where opportunity and danger danced a nightly tango — where you could make a fortune in a back-alley card game, or lose your life for looking at the wrong person the wrong way. This was the world that was waiting. A labyrinth of power, vice, and desperation.

And in the heart of this bustling, and at times treacherous, metropolis, stood the Hotel President. Opened just eight years earlier, it was a fifteen-story testament to the city's ambition. Its lobby was a symphony of polished marble, ornate plasterwork, and gleaming brass. It was home to the Drum Room, a legendary nightclub that would later host stars like Frank Sinatra and Benny Goodman. The President was a crossroads, a place for travelers of all kinds. From the wealthy cattle baron closing a deal, to the weary salesman hoping for a soft bed, to the shadowy figures of Pendergast's syndicate conducting their business over cocktails. Every guest who walked through its revolving doors carried their own story, their own secrets.

But on the afternoon of Wednesday, January 2nd, a man with a story that would outlast them all walked into that opulent lobby. He was young, probably in his twenties. He was of medium height and build, with dark brown hair and a deep, noticeable scar that snaked across the left side of his scalp, disappearing into his hairline. He also had a cauliflower ear, the gnarled, thickened cartilage that marked him as a boxer or a wrestler. He was dressed neatly, if inexpensively, in a dark overcoat, a simple suit, and polished shoes. But what was most striking about him was what he didn't have. He carried no luggage — no suitcase, no travel-worn trunk, not even a briefcase. In an era of rail travel and extended stays, a man arriving at a fine hotel with nothing but the clothes on his back was an anomaly, a detail that couldn't help but be noticed.

He approached the front desk with a steady, unhurried gait. The clerk, taking in the man's appearance, saw nothing overtly concerning, just unusual. The man requested an interior room on a high floor. Not a room with a view of the city, but one that faced inward, looking out onto a brick air shaft. He wanted privacy. He wanted to be away from the noise and the eyes of the street below. He signed the register with a confident, looping script. "Roland T. Owen, Los Angeles". He paid for one night's lodging in cash.

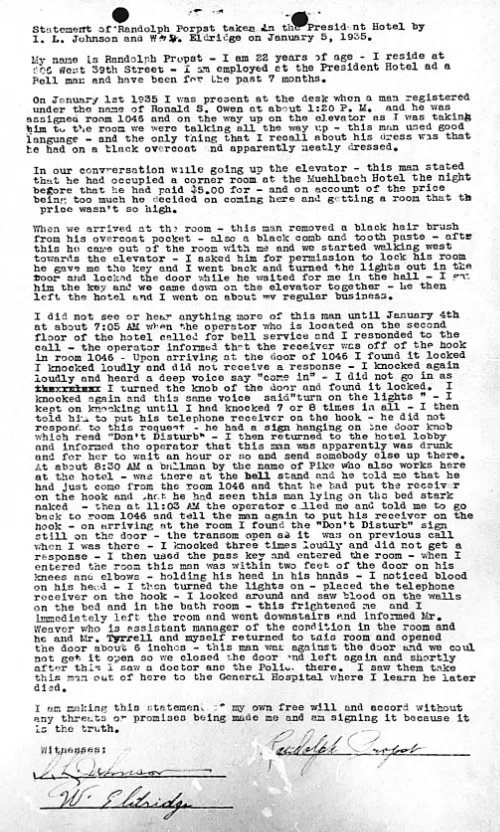

The bellboy assigned to him was a young man named Randolph Propst. The bellboy, accustomed to the oddities and demands of hotel guests, thought little of the lack of luggage at first. Perhaps the man's bags were delayed, or he was only in town for a few hours. Propst led the guest to the elevator, the silence between them punctuated only by polite smalltalk as they ascended. The guest complained about the prices at the hotel next door, claiming he'd stayed there the previous night, and found it far too expensive at $5 a night.

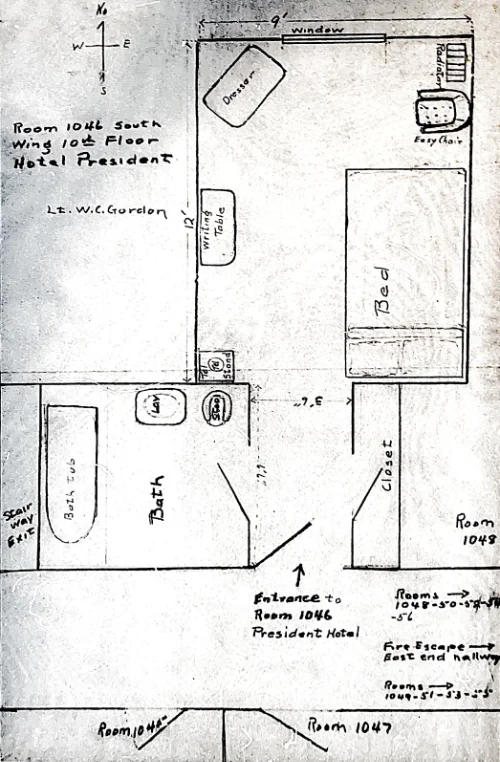

They stepped out of the elevator on the tenth floor. They walked down the long, carpeted hallway to room 1046. The room itself was unremarkable, a standard single of its time: a bed, a heavy wooden desk and chair, a floor lamp, and a small on-suite bathroom. The single window offered a drab, lightless view of the hotel's inner courtyard. It was a room designed for anonymity.

As Propst opened the door and turned on the lights, he watched as Mr. Owen conducted his version of unpacking. From the deep pockets of his overcoat he produced a comb, a hairbrush, and a tube of toothpaste. He placed them neatly on the small glass shelf above the sink in the bathroom. And that was it. That was the entirety of his luggage, the sum total of his worldly possessions for his stay at the Hotel President.

Propst handed Owen the key, and as he was turning to leave, Owen made one final, peculiar request. "Could you leave the door unlocked?" he asked. His tone was casual, matter-of-fact. "I'm expecting a friend in a few minutes." This was another strange detail. Guests, especially those in a city like Kansas City, prized their security. But Propst was paid to accommodate, not to question. He nodded, pulled the door, leaving it unlocked, and returned to the lobby.

He saw Owen leave the hotel a short time later, coat collar turned up against the winter chill. For a few hours, the strange guest in 1046 was just another face in the crowd, another temporary resident of the city. But as the day bled into a cold January night, the story of Roland T. Owen began to take a dark and twisted turn — a turn that would leave a permanent stain on the history of the hotel, and a permanent mystery in the annals of American crime.

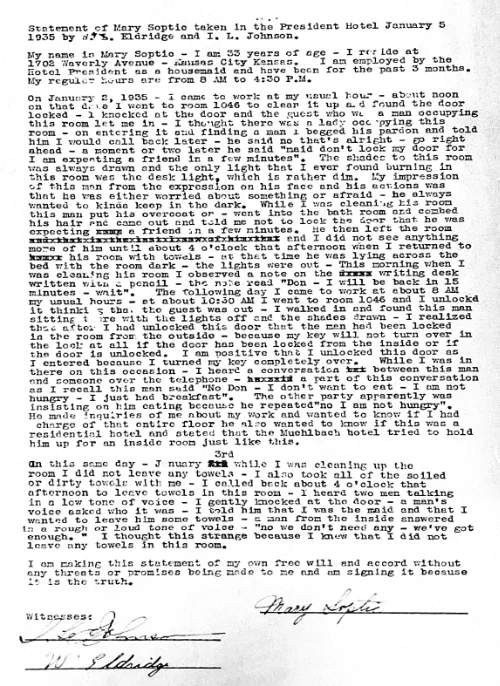

The first threads of the unraveling story of room 1046 came not from a single, dramatic event, but from a series of small, unsettling observations made by the hotel staff, the people whose jobs required them to be both present, and invisible. The primary witness to these strange occurrences was a maid named Mary Soptic. Her shift began in the afternoon. On that Wednesday, January 2nd she made her way to room 1046 for the routine daily cleaning. She knocked and heard a voice from within tell her to enter. She opened the door to a scene of profound stillness. The room was shrouded in darkness. The heavy curtains over the single window were drawn tight, blocking out what little daylight could penetrate the air shaft. The only illumination came from a single, small lamp on the desk, casting long, distorted shadows across the room.

And in the center of that gloom, sitting in a chair, was Roland T. Owen. He wasn't reading. He wasn't writing. He was just sitting, staring into the dimness, as if waiting.

Mary felt a prickle of unease. He seemed nervous, his body coiled with a restless energy that felt out of place in the silent room. He told Mary she could go ahead and clean, and as she worked, moving quietly around him, he spoke again, his voice low but firm. He reiterated his earlier request to the bellboy: leave the door unlocked. "I'm still waiting for my friend," he explained, though his explanation did little to ease Mary's sense of foreboding. She finished her work, backed out of the room, and closed the door, leaving it — as instructed — unlatched.

Later that same day, around 4 o'clock, Mary returned to the tenth floor with a delivery of fresh towels. When she entered room 1046, its curtains still drawn, she saw Owen lying on the bed, fully clothed, in the dim light. She left the towels in the bathroom, and turned towards the door. Before she left, Mary's eyes fell upon the writing desk. Beside the lamp, there was a small note, written on hotel stationery.

It read: "Don, I will be back in fifteen minutes. Wait."

The next day, Thursday, January 3rd, the strangeness escalated. When Mary arrived to clean room 1046, a "Do Not Disturb" sign hung from the doorknob. She found the door was not just locked, but it was locked from the outside. This was a significant, and baffling, detail. A guest could lock their door from the inside, but to lock it from the outside required a key. It implied someone had left the room and locked Owen inside. Mary, using her master key, let herself in. The scene was eerily similar to the day before. The room was dark, the curtains drawn, the single lamp casting its weak, yellow glow.

And there, in the chair, was Roland T. Owen. He looked as though he hadn't moved. He seemed even more agitated than the previous day — a man trapped not just in a room, but in a state of high anxiety. As Mary began to clean, the telephone on the desk rang, its shrill cry shattering the silence. Owen picked up the receiver. Mary, working nearby, couldn't help but overhear his side of the conversation. It was tense, and it was brief.

"No, Don," Owen said, his voice sharp with frustration. "I don't want to eat. I'm not hungry. I just had breakfast."

There was a pause as the person on the other end spoke. "No," Owen repeated, more forcefully this time. "I am not hungry."

He slammed the receiver back into its cradle. He seemed shaken. He turned to Mary, and for the first time he seemed to try to engage her in a real conversation. It felt forced, a desperate attempt to create a veneer of normalcy over a situation that was clearly anything but. He asked her about her job — if she was responsible for the entire floor, and if the hotel had residential guests. To Mary, it sounded like the rambling of a man trying to distract himself, a man on the run from something, or someone. He was afraid, she realized. Deeply afraid.

At around 4 o'clock, Mary again returned to the tenth floor with a pile of fresh towels. As she reached 1046, she knocked lightly on the door. "Go on in," a voice called from inside. But it wasn't Owen's voice. This voice was different — deeper, rougher, with a gruff, intimidating edge. Confused, Mary knocked again, announcing that she had fresh towels. "We don't need any," the gruff voice snapped back. Mary, unnerved and not wanting to intrude on what was clearly a private meeting, quickly moved on, leaving the towels outside the door. Who was this other man? Was this the friend Owen had been so anxiously awaiting? The note, the phone call, the gruff voice, the man locked in his own room from the outside. It was an accumulation of contradictions and danger signs. Mary finished her work and left, deeply unsettled by the man in the dark room. She would be the last person, aside from his killer, to see Roland T. Owen alive and uninjured.

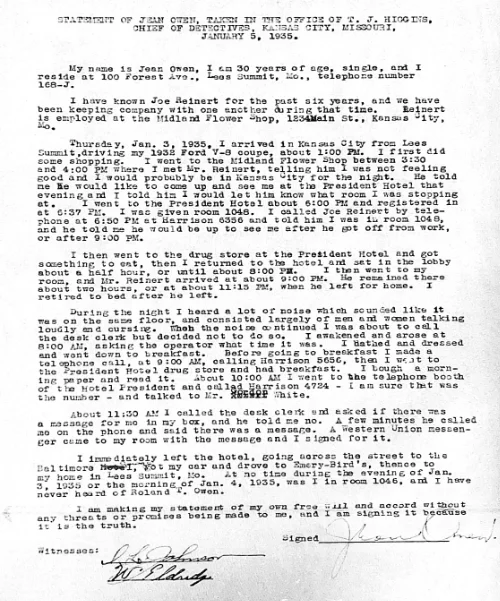

As evening fell on the tenth floor of the Hotel President, the sounds of trouble began to filter through the walls. A guest in the adjacent room 1048, a woman named Jean Owen — an unsettling coincidence of name, but no relation — was in her room for the night. Sometime after 11 o'clock, she became aware of loud voices coming from 1046. It wasn't just a conversation, it was an argument. She could clearly distinguish the voices of a man and a woman talking loudly, their words punctuated by curses. She heard scuffling, the sound of people moving, perhaps struggling. Then, a distinct, sharp sound. A gasp, or a cry of pain. But in the bustling, often raucous environment of a large downtown hotel, such noises were not entirely uncommon. People fought, people drank, people made noise. Not wanting to get involved, Jean Owen tried to ignore it. The noises eventually subsided, and an uneasy quiet settled over the hallway once more.

As the strange, tense drama played out within the walls of room 1046, another scene was unfolding just a few miles away, a fleeting encounter on the cold, dark streets of the city. At around 11 o'clock that same night, a city worker named Robert Lane was driving his car down 13th Street. Suddenly, a figure darted from the shadows and into his headlights, flagging him down with desperate urgency. The man was shockingly underdressed for the biting January air, wearing only an undershirt, pants, and shoes. Lane slammed on his brakes. The man rushed to his window, apologizing breathlessly, saying he'd mistaken Lane's car for a taxi. He seemed agitated, desperate, and asked for a ride to somewhere he could find a cab. Lane, perhaps out of pity or simple Midwestern decency, agreed. As the man slid into the passenger seat, Lane couldn't help but remark, "You look as if you've been in it bad."

The man didn't deny it. His reply was a low, chilling promise, a vow muttered into the darkness of the car: "I will," he swore, "I will kill them tomorrow."

In the rear-view mirror, Lane caught sight of a deep, angry scratch on the stranger's arm. He was cupping his other arm strangely, as if trying to catch blood from a wound Lane couldn't see. The air in the car was thick with fear and violence. Lane drove them to the intersection of 12th and Troost, a corner where cabbies often gathered. The man thanked him, got out, and confidently strode to a parked taxi, honking its horn to summon the driver from a nearby diner. As Lane drove away, the image of the strange, wounded man and his venomous promise lingered, a loose thread in the night's already tangled web.

The morning of January 4th, 1935.

A new day dawned over Kansas City, and the mystery in room 1046 deepened. Around 7 o'clock, the hotel's switchboard operator noticed that the phone in 1046 had been off the hook for some time, tying up the line. Following procedure, she dispatched a bellboy to check on the room. The bellboy was Randolph Propst, the same young man who had checked Owen in just a day and a half earlier. Propst took the elevator to the tenth floor. The hallway was quiet. The door of 1046 had a "Do Not Disturb" sign hanging from it. Propst knocked. There was no answer. He knocked again, louder this time, announcing himself. "Bellboy!"

After a long pause, a voice from inside called out. It was a low, slurred voice — the kind Propst associated with a guest who'd had too much to drink. "Come in," the voice mumbled. "Turn on the lights."

But the door was locked. Propst tried the handle, but it wouldn't budge. He knocked again, several times. There was no response. He waited, listening at the door, but heard nothing more. Assuming the guest was drunk and had passed out, Propst gave up. He shouted through the door, "Your phone is off the hook!" and then returned to the lobby, telling the switchboard operator she should send someone to try again later, when the guest might have sobered up.

An hour and a half later, around 8:30, the light for room 1046 was still illuminated on the switchboard. The phone was still off the hook. This time another bellboy, a man named Harold Pike, was sent up. Pike carried a master key. He knocked first, as a courtesy, but received no answer. He inserted the key, turned the lock, and pushed the door open into absolute darkness. The heavy curtains were still drawn tight. The only light was the weak glow from the hallway spilling in behind him. As his eyes adjusted, he could just make out a figure on the bed. It was a man, lying naked. Pike could see that the phone stand next to the bed had been knocked over. He assumed the sleeping guest had rolled over and dislodged the receiver. He saw the man's silhouette, the rise and fall of his chest. He was breathing heavily, a deep, labored sound that Pike also attributed to a drunken stupor. In the faint light, Pike noticed a dark spot on the sheets near the man's head, but dismissed it as a shadow. Not wanting to disturb the guest any further, Pike worked quickly and quietly. He reached into the room, righted the phone stand, and placed the receiver back in its cradle. Then he backed out, pulling the door closed behind him. He didn't lock it. He simply left, his task complete.

But the silence in room 1046 was not the silence of a drunken sleep, it was the silence of something far more sinister. The labored breathing was not from intoxication, but from a punctured lung. And the dark spot on the sheets was not a shadow, it was blood. The final, horrifying chapter of the story of Roland T. Owen was about to be written.

Around 10:30 AM, the switchboard operator sighed with exasperation. The light for room 1046 was on again. The phone was back off the hook. She sent Randolph Propst to find out what was happening. For the third time in three days, the young bellboy made his way to room 1046, a growing sense of unease settling in the pit of his stomach. This guest, this room, it was all wrong. He knocked loudly on the door, ignoring the "Do Not Disturb" sign. "Bellboy!" he called out.

He waited. Silence. He knocked again, pounding his fist on the heavy wood. Still nothing. The silence from within was absolute, and suddenly, profoundly unnerving. Using his master key, Propst unlocked the door and pushed it open. What he saw would stay with him for the rest of his life, a waking nightmare seared into his memory.

The room was a slaughterhouse. Blood was everywhere. It was spattered high on the walls, a dark, abstract pattern of violence. It was soaked into the bedding, turning the white sheets a deep, rusty brown. It was pooled on the floor. The air was thick with the coppery, metallic smell of it. And there, in the middle of the chaos, was Roland T. Owen. He was on the floor between the bed and the bathroom, on his knees and elbows, his head cradled in his hands as if he were in prayer, or simply too broken to hold it up any longer. He was naked, his body a canvas of bruises and cuts. He was covered, head to toe, in drying blood.

Propst froze for a second, his mind unable to process the horror before him. Then, primal fear took over. He turned and fled, his heart hammering against his ribs, his breath catching in his throat. He didn't wait for the elevator. He sprinted down the stairs, bursting into the lobby, his face pale with shock. He found the assistant manager, his words tumbling out in a panicked stammer: "Room 1046, there's a man in there, he's hurt. Badly."

The hotel manager immediately called the police. Within minutes, the tenth floor of the Hotel President was swarming with officers and detectives from the Kansas City Police Department, led by Detective Ira Johnson and Sergeant Frank Howland. They stepped into room 1046 and entered a scene of unimaginable brutality. The man who called himself Roland T. Owen was still alive, but just barely. His breathing was a shallow, rattling gasp. The detectives, and a doctor who'd arrived on the scene, saw the full extent of his injuries. He'd been bound, tightly, with a thin, white cord around his neck, his wrists, and his ankles. The knots were amateurish, but brutally effective, cutting deep into his flesh. The cord itself was stained a deep, dark red. He'd been stabbed multiple times in the chest, the wounds clustered above his heart. One had been deep enough to puncture his lung. His skull was fractured from at least three severe blows to the head, likely delivered with a heavy, blunt object. His neck was covered in dark bruises, clear evidence that his attacker had also tried to strangle him. He had been systematically and sadistically tortured over a period of many hours. In the bathroom, the scene was just as grim. The detectives found more blood smeared on the floor and the sides of the tub. A single, shattered water glass lay in the sink.

Miraculously, through the haze of shock and pain, he was still conscious. As the doctor worked to stabilize him, Detective Johnson knelt beside him, trying to get him to talk. "Who did this to you?" he asked, his voice gentle but firm. "Who was here with you?"

Through swollen, cracked lips, the dying man managed to whisper a single, baffling word. "Nobody."

The detectives pressed him. "Then how did this happen? You have to tell us."

He stirred slightly, his eyes fluttering. "I fell," he rasped, his voice barely audible. "I fell against the bathtub."

It was the last thing he would ever say. Shortly after, he slipped into a coma. An ambulance rushed him to the hospital, but his injuries were far too severe. In the early hours of January 5th, the man who had checked into the Hotel President as Roland T. Owen was pronounced dead. And with his death, the investigation into the impossible, brutal mystery of room 1046 began.

The investigation into the murder of the man in room 1046 was a study in frustration and bizarre contradictions. Detectives Johnson and Howland were faced with a crime scene that was both incredibly violent, and strangely — almost surgically — devoid of meaningful clues. It was as if the killer, or killers, had taken meticulous care to erase themselves, and their victim, from existence. There was no murder weapon. The police searched every inch of the room, but found nothing that could have inflicted the deep stab wounds, or the crushing blows to the head. The cords that had been used to bind the victim were common, everyday items, utterly untraceable.

Most perplexing was what was missing. All of the victim's clothing was gone — his suit, his shirt, his shoes, his dark overcoat. All vanished. Also missing was the soap from the bathroom dish, the hotel towels, even the toothpaste and brush he had placed on the shelf. Why would a killer bother to take such mundane items? The only logical conclusion was that they were trying to prevent identification. The clothing might have had laundry marks, or tailor's labels. The other items might have held fingerprints. It was a clear, deliberate effort to make the victim a "John Doe".

What little evidence the police did find only deepened the mystery. Tucked away in a corner of the room, they found a single, unsmoked cigarette. Lying on the floor was a small hairpin. In the bathroom, a safety pin. And on the telephone stand, detectives managed to lift four fingerprints from the glass surface. They were small, the police noted — small enough to belong to a woman. They didn't match the victim, or any of the hotel staff who'd been in the room. In an age before computerized databases, the fingerprints were a ghost's signature, a tantalizing clue that led absolutely nowhere. But perhaps the strangest, most intriguing piece of evidence found in that room was a full bottle of diluted sulfuric acid.

And then there was the identity of the victim himself. The name Roland T. Owen and the Los Angeles address were quickly revealed to be a dead end. There was no record of any such person living in Los Angeles, or in Kansas City. The name was an alias, a carefully chosen fiction. The man in room 1046 was officially a John Doe.

The case, with its gruesome details and locked-room mystery, became an immediate sensation in Kansas City. The newspapers ran sensational headlines: "Unidentified Man Dies After Torture", "Mystery Veils Torture Killing". The public was captivated. The story had everything: a fine hotel, a mysterious stranger, brutal violence, and no apparent motive.

The body was taken to a nearby funeral home. In a macabre practice that wasn't uncommon for the time, the body was embalmed and put on public display, in the desperate hope that someone, anyone, would recognize him. Over the next few weeks, hundreds of Kansas City residents filed past the cold, silent body, their faces a mixture of morbid curiosity, civic duty, and genuine sympathy, all drawn by the city's most sensational murder.

Among them was a man with a nagging memory. It was Robert Lane, the city worker who had given a ride to a desperate stranger just a few nights before. As he looked down at the cold, still face of the man who'd been making headlines for days, his eyes were drawn to the man's arm. There it was. The same deep, angry scratch he had seen in the dim light of his car. Convinced he held a key to the mystery, Lane went straight to the police. He told them everything: the man in the undershirt, the desperate plea for a taxi, the chilling vow of revenge. But while Lane was certain, the police were skeptical. His story, however compelling, created a logistical puzzle they couldn't solve. No one at the Hotel President — no doorman, no clerk, no bellboy — had seen Owen leave the hotel that night, nor had they seen him return. How could a man in that state — bleeding and underdressed — slip out, and back in, completely unnoticed? Was Robert Lane's passenger the man from room 1046, or another man entirely, whose own tragic story briefly intersected with this one, before vanishing back into the night?

The police chased down dozens of false leads. A man from a neighboring town was certain the body was his missing cousin, only to have his sister arrive and confirm that the cousin had, in fact, died five years earlier. A wrestling promoter from Arkansas thought he recognized the cauliflower ear, and claimed the man was a wrestler who went by the name Cecil Werner. But that, too, proved to be a false trail. Days turned into weeks, and the man in room 1046 remained nameless, his story a blank page. The police were no closer to finding his killer than they had been on the day his body was discovered.

As the weeks turned into months, it seemed that the man would be buried without ceremony in a pauper's grave, his story unfinished, his identity lost to time. But then, another strange twist, in a case that was already full of them. The funeral home received an anonymous phone call. A man, who refused to give his name, asked that the dead man who'd been in the news be given a funeral, and a burial plot at Memorial Park Cemetery. He said he'd be sending money to cover the funeral costs. The undertaker asked the caller what his connection was to the case. "Cheaters usually get what's coming to them," the man said with cold finality, and then he hung up. A few days later, a plain envelope arrived. Inside was a wad of cash, wrapped in a newspaper — enough to cover the cost of the funeral and the burial plot.

Then came another call, this time to the Rock Flower Company. The caller requested that a bouquet of 13 American Beauty roses be placed on the man's grave. As before, the payment for the flowers arrived in a plain envelope, this time with a small, white card with a simple inscription, its handwriting obviously disguised. It read: "Love forever. Louise."

The man in room 1046 was buried in Memorial Park Cemetery, his funeral surrounded by as much mystery as his death.

The police now had a few more cryptic clues — a grieving lover named Louise, perhaps a vengeful brother — but they were no closer to solving the mystery of who he was, or who had killed him. He was a ghost in the city's memory, a victim without a name, a murder without a motive.

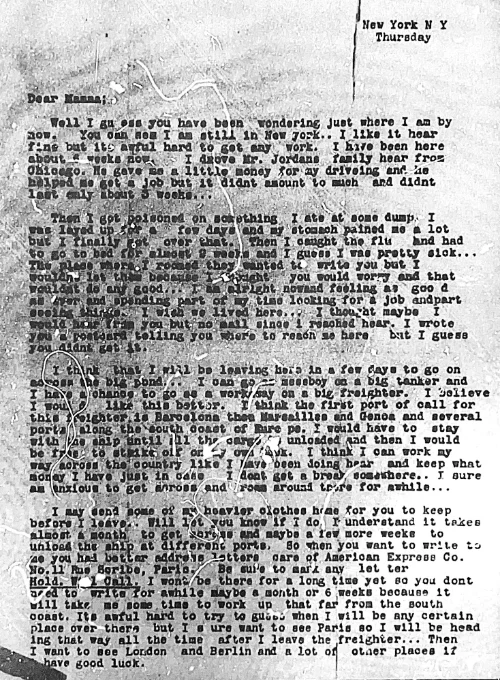

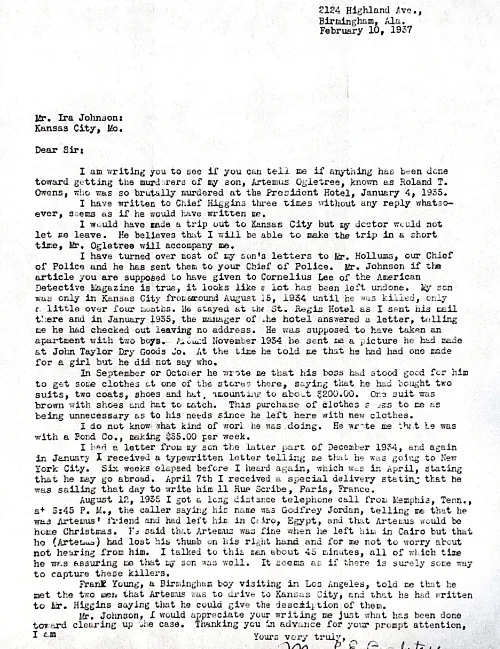

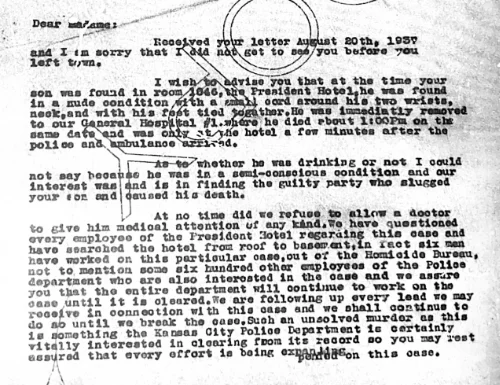

But the story was not over. For more than a year, the man in the grave remained a mystery to the world. But to a mother in Birmingham, Alabama, his absence was a constant, gnawing presence. Ruby Ogletree's life had been consumed by a quiet, gnawing worry ever since her son, Artemus, had left home in 1934. The sporadic letters from his travels had been a comfort, but in the spring of 1935, their nature had changed completely. The new letters were typewritten, their language stilted and alien, telling increasingly bizarre tales of trips to Europe, and a sudden, wealthy marriage in Egypt. Ruby's maternal intuition screamed that something was wrong. Her fears were amplified by a strange and deeply unsettling phone call. The man on the other end of the line identified himself as Godfrey Jordan. They spoke for 45 minutes, his words often wild and irrational. Yet, amidst the strange ramblings, he seemed to possess an intimate first-hand knowledge of her son. He reiterated the story about Egypt, and offered a sinister explanation for the typewritten letters: Artemus, he claimed, had lost a thumb in a fight, and could no longer write by hand.

Ruby listened, her blood running cold, because she was convinced the voice on the phone was not a stranger named Godfrey Jordan. She believed it belonged to Joe Simpson, a young man from Birmingham, a friend with whom Artemus had left home two years earlier. The thought that her son's own friend could be part of such a cruel deception galvanized Ruby. Her worry transformed into a desperate, determined investigation. By November of 1935, she was writing to anyone she thought could help. She wrote to the State Department to see if a passport had been issued for Artemus. She wrote to customs authorities to see if he could have set sail without one. She sent a letter to the American consulate in Cairo, pleading for any information. She even contacted the FBI. Each reply was a dead end, a door closing on her hope. As the new year of 1936 dawned, her desperation reached its peak. In January, Ruby Ogletree sat down and wrote a letter to the most powerful man in the country: President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

"I fear he has fallen into some gang, or something has happened to him," she wrote, a mother's heart laid bare on the page. "He has always been a good boy and has high ideals. I simply must find some trace of him. If he is in trouble I want to know."

It was just a few weeks after she sent that letter, after nearly a year of frantic searching, that a friend handed her a copy of the American Weekly magazine. As she turned the pages, an article caught her eye. It was about an unsolved murder in Kansas City, the strange story of a man who had been found tortured and killed in a hotel room. The article included a police sketch of the victim, Roland T. Owen. Ruby stared at the image, her breath catching in her throat. The man in the sketch looked so much like her son. Then she read the description: a distinctive scar on the left side of his scalp. The terrible truth crashed down upon her. It was the same scar her son had gotten as a small child, when a pan of hot grease had spilled on him.

With a heart filled with a mixture of hope and dread — hope that it wasn't him, dread that it was — she contacted Kansas City police. The description she provided was a perfect match, and after the body was exhumed, her worst fears were confirmed. The man in room 1046 was her son Artemus. Ruby now knew her son's fate, but her search wasn't over. It simply had a new focus. She never let go of her suspicion of Joe Simpson, the friend she believed had called her from Memphis. She wrote to the Kansas City detectives, explicitly naming him as a person of interest. She became a detective herself, obtaining Simpson's school records from Phillips High School, looking for any clue. For years, she tried to arrange a meeting with him in Birmingham, only to be stood up time and again. The police politely assured her that Simpson had been interviewed, and was not a suspect. But Ruby was undeterred. Finally, on December 28th, 1939, nearly five years after her son's murder, she managed to confront him. The meeting only hardened her conviction.

"In talking with the boy, Joe Simpson, I was reasonably convinced that he is the person that talked to me from Memphis, Tennessee, seven months after my son was killed," she later wrote to the Kansas City police, her letter a testament to a mother's unyielding quest for justice.

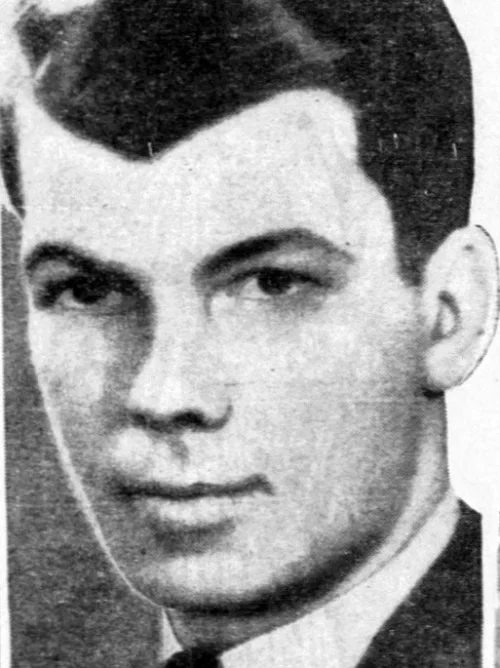

The man in room 1046 was not Roland T. Owen. He was Artemus Ogletree, a 19 year-old boy from Birmingham, Alabama, who'd been looking for adventure, and had instead found a brutal and mysterious end.

The identification of Artemus Ogletree was a major breakthrough in the case, but it also raised a host of new, even more disturbing questions. Why was he in Kansas City, so far from home? Why was he using a fake name? Who was the mysterious "Don" he was supposed to meet? Who was the man he spoke to on the phone? And most chillingly, who had sent those typewritten letters to his mother? The letters weren't just a lie, they were a calculated act of cruelty, sent months after Artemus was already dead, meant to stop his family from looking for him. The killer, or someone connected to the killer, was not just violent, they were cunning and sadistic.

The police now had a name, but they were no closer to finding a killer. The trail was now over a year old. The clues were sparse, and the witnesses' memories were fading. The investigators' instincts had by now distilled into a handful of theories. Some believed that this was a crime of passion — a love affair that had soured into murderous rage. The evidence for this is compelling, if circumstantial. There were the woman's fingerprints found on the telephone stand. There was the hairpin found in the room. There was the testimony of Jean Owen in room 1048, who distinctly heard a man and a woman arguing loudly, just hours before the attack. And then there are the events after his death. The anonymous call to the undertaker could have been from the brother of "Louise", who'd sent the bouquet of 13 roses to his funeral. Who was Louise? Was she the woman in the room? Was she the one who argued with Artemus, the one who left her hairpin and fingerprints behind? In this scenario, "Don" could have been another woman. Donna, perhaps, a woman Artemus was meeting behind Louise's back — a secret meeting for which he would prefer to use a false name in the hotel register. Perhaps the gruff voice Mary Soptic heard belonged to the angry brother, a man seeking vengeance for his sister's honor. The argument escalates, the brother gets involved, and things spiral violently out of control. The torture could have been a furious, uncontrolled expression of rage. Or perhaps a similar story played out, but with Artemus and the anonymous caller as rivals for Louise's affections.

But other detectives felt the crime didn't fit the profile of a spontaneous, rage-fueled killing. The removal of evidence at the scene, and the fake letters to Ogletree's mother for months after his death, suggest a level of cold, detached planning that points in a different direction. And how had the bottle of acid appeared in the hotel room? If it was brought by the killer, that suggests they had sinister intentions from the outset.

Some investigators had a hunch that the mob was behind the murder. This was Tom Pendergast's Kansas City, after all: organized crime was a part of the city's bones. The name "Don" could conceivably have been a title, not a name — a reference to a mafia boss. Perhaps Ogletree, a young man looking for quick money, had gotten involved as a low-level courier or a bagman. Perhaps he was entrusted with something — money, information, or illicit goods — and had either lost it, stolen it, or was planning to sell it to a rival faction. This theory neatly explains several key elements of the crime. The extreme torture would be consistent with a mob interrogation, a brutal attempt to extract information or the location of missing property. The systematic cleanup of the room — removing the body's identification and any personal effects — is the hallmark of a professional hit, designed to send a message while leaving the police with nothing to go on. The bottle of acid could have been brought to remove Ogletree's fingerprints, to further hamper identification. Perhaps the killer was disturbed before having chance to use the acid, and fled after cleaning up the room, forgetting to bring the bottle with him, his careful plans having been disrupted. Ogletree's final words, "Nobody... I fell against the bathtub", could have been his last act, abiding by the criminal code of silence, knowing that naming his attackers would only bring more trouble to himself or his family. The mob might have been behind the anonymous payment for his burial plot, the ultimate act of cynical power. A final, chilling gesture that offered the appearance of a proper burial, while ensuring that the truth of their involvement was silenced forever beneath a headstone they themselves had paid for. The investigation, however, failed to find any evidence to connect Artemus Ogletree, a teenager from Alabama, to any known criminal organization in Kansas City, or anywhere else. He was a drifter, not a gangster.

One of the lead investigators on the case, Detective Chief T.J. Higgins, became convinced by a different, chilling theory, one that suggests the evil that visited room 1046 was not a singular event, but part of a larger, darker pattern. It's a theory that stretches across state lines and through the years, connecting the death of Artemus Ogletree to a gruesome murder in New York City, and to a predator who may have passed through Kansas City like a ghost, leaving only tragedy in his wake. To explore this, we leave Kansas City in 1935, and travel forward two years, to the summer of 1937. In a New York City rooming house, Joseph Martin, a man with a shadowy past, murders his roommate, Oliver George Sinecal. Sinecal was no innocent — newspapers described him as a small time thief and narcotics pedlar — but the manner of his death was horrific. Martin shot Sinecal, then dismembered his body. He carefully cut away a distinctive tattoo from Sinecal's arm, then stuffed the nude corpse into a large steamer trunk, addressed it to Memphis, Tennessee, and arranged for its shipment from Penn Station. But the trunk was flagged for its suspicious weight, and the foul odor escaping from it. It was opened, the gruesome contents were discovered, and just seven hours later, Joseph Martin was in police custody. The case revealed Martin to be a cold, methodical killer, a man who took deliberate steps to erase his victims' identities. But what interested investigators was his use of aliases. And one of his preferred names was "Donald Kelso". The name Donald Kelso sent a jolt through the investigators in Kansas City, who were still haunted by the Ogletree case. They immediately scoured their own records, poring over the dusty hotel registration cards from the months leading up to the murder. And then they found it. A registration card from a different Kansas City hotel, dated before the murder. On it were two names, two men who had checked in together. The first was Donald Kelso. The second was a name that couldn't possibly be a coincidence: Duncan Ogletree.

The similarity was staggering. Duncan Ogletree checking in with Donald Kelso. Artemus Ogletree waiting in a hotel room for a man named Don. For the Kansas City police in 1937, it felt like the key that could finally unlock the entire mystery. They obtained a copy of Joseph Martin's signature, and compared it to the looping script of Donald Kelso on the old hotel registration card. At the time, they were convinced they had a match. The news must have felt like a breakthrough. For a moment, the ghost who'd been in room 1046 had a face, and it belonged to the killer in a New York jail cell.

But stories like this are rarely so simple. For over a decade, the link seemed plausible, a widely accepted footnote to the unsolved case. Detective Chief Higgins eventually proclaimed that he was satisfied that Joseph Martin was, indeed, the killer of Artemus Ogletree. Then, in 1950, the FBI reviewed the cold case file. Their own document examiners, with more advanced techniques at their disposal, took another look at the handwriting. Their conclusion was a stunning reversal of the original finding. The signature of Donald Kelso, they determined, was not a match for the handwriting of Joseph Martin. This finding shatters the theory, yet leaves the terrifying coincidences hanging in the air. The FBI's analysis contradicts what seems to be an impossible coincidence. How could a man named Duncan Ogletree check into a hotel with a Donald Kelso, just before Artemus Ogletree is murdered while waiting for a man named Don, if there was no link? Was the Kansas City Police Department's initial analysis simply a case of wishful thinking, of seeing a pattern where none existed? Was Chief Detective Higgins put under pressure to steer the investigation away from the organized crime angle? The Director of the Kansas City Police Department, appointed under Tom Pendergast's influence, had connections to the mob, and the police department had become rife with corruption. Or is there another explanation, one that we can no longer uncover?

Perhaps the most popular theory among detectives, and a fascinated public — many of whom wrote letters to the police after reading about the case in detective magazines — was that this was a sexual encounter turned violent. There were reports from police at the time of a "commercial woman" — a prostitute — who was seen in the area, and who may have been connected to the case. She was reportedly seen at a bar with a man matching Ogletree's description earlier in the evening. Perhaps the meeting in room 1046 was a transaction that went wrong. The argument could have been over money. The gruff voice Mary Soptic heard could have belonged to a violent pimp who arrived to find a dispute, and escalated it to torture and murder. This would account for the hairpin, the woman's fingerprints, and the argument.

Others speculated that Ogletree's clandestine encounter was not with a woman, but with a man. In the 1930s, this was not just deeply taboo, but illegal. Perhaps Don was his lover. The argument Jean Owen heard could have been a lover's quarrel. The brutal, personal nature of the attack — the binding, the stabbing — is often seen in crimes of intense, personal rage, not detached, professional violence. Or perhaps Artemus had been lured to the encounter by a man intent on a violent, homophobic attack, or to blackmail Artemus, demanding money in order to keep his secret — a shakedown attempt that, when unsuccessful, prompted a violent punishment. And Ogletree's refusal to name his attacker, even as he lay dying, could be seen as the ultimate act of self-preservation, not of his life, but of his secret. To him, revealing the truth might have been a final shame he was unwilling to endure.

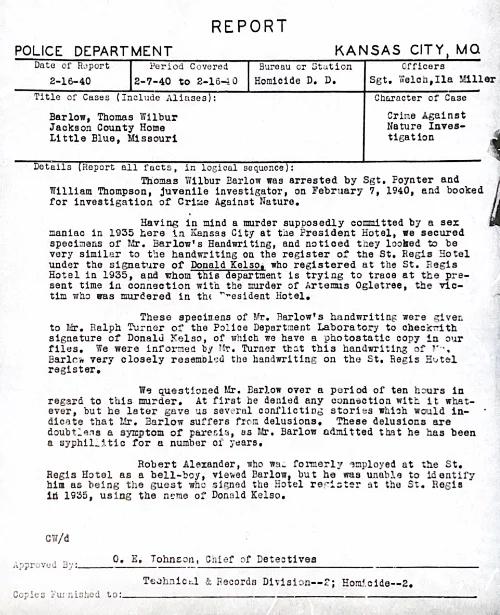

This theory led investigators down a dark and winding path. Men across the country, often with little more than innuendo to connect them to the case, were fingerprinted, questioned, and asked for handwriting samples. One of the most striking examples of this occurred in 1940, when detectives investigated a man named Thomas Wilbur Barlow, who had been convicted of, in the parlance of the time, "crimes against nature" in Little Blue, Missouri. The arresting officers, noting a similarity between Barlow's signature and that of Donald Kelso on the hotel registry, believed they might have found their man. Barlow was subjected to a grueling 10 hour interrogation, during which he gave several confusing and conflicting stories. But instead of a confession, the police were left with only confusion, which they ultimately, and tragically, chalked up not to the duress of the interrogation, but to the degenerative effects of syphilis on Barlow's brain. Another suspect lost to the fog of a frustrating and inconclusive investigation.

All of these theories remain speculation, an attempt to read between the lines of a story with too many pages missing.

Nearly a century has passed since the death of Artemus Ogletree. The Hotel President still stands in Kansas City, its walls holding the memory of a tragedy that unfolded on its tenth floor. The world has changed in countless ways. Forensic science has leapt into a future the detectives of 1935 could barely have imagined. And yet, the mystery of room 1046 remains frozen in time, a chilling tableau of a life cut short and a crime that has never been solved.

Who was the gruff-voiced man in the room? Who was the mysterious Don? Was he a lover, a gangster, a pimp, or a serial killer? Who was the woman who left her fingerprints on the phone, and her hairpin on the floor? Who was Louise, the woman who sent thirteen roses to the funeral of a man she may or may not have known? And why was a young man from Alabama, so far from home, subjected to such a brutal, sadistic, and agonizing death?

We may never know the answers. The people who held the secrets of room 1046 — the killer, the accomplice, the witnesses — are long gone, their stories buried with them. All that remains is a story that continues to intrigue us. In the end, Artemus Ogletree is a victim without justice, a young man whose final moments were a symphony of pain and fear, and whose final words were a lie — "Nobody, I fell against the bathtub" — a desperate attempt to protect a secret that he ultimately took with him to his grave.

For a year and a half, he was a nameless face. Today, we know he was a son. He was a brother. He was a 19 year-old boy who left home seeking adventure. He should not be remembered simply as "the man in room 1046". He should be remembered as the boy who was lost, and then found. but whose story could never be fully told.

More Episodes

The Green Bicycle Case

In the summer of 1919, a young woman named Bella Wright was found dead on a quiet country lane in Leicestershire, a bullet wound in her head. The only clue? A mysterious, well-dressed man seen with her shortly before her death, riding a distinctive green bicycle. Read more

The Killing of Maximum John

In May 1979, the American justice system was shaken to its core. Federal Judge John H. Wood Jr. — known by criminals as "Maximum John" for the harsh sentences he handed down — was shot and killed by a sniper outside his San Antonio home. Read more