The Green Bicycle Case

In the summer of 1919, a young woman named Bella Wright was found dead on a quiet country lane in Leicestershire, a bullet wound in her head. The only clue? A mysterious, well-dressed man seen with her shortly before her death, riding a distinctive green bicycle.

This episode explores one of Britain's most enduring unsolved murders. We trace the police investigation that led to the arrest of a respectable schoolteacher, and the sensational trial that followed. Was it a tragic accident, or a callous murder?

In the quiet summer of 1919, just months after the guns of the Great War fell silent, a young woman set off on her bicycle down a lonely country lane in Leicestershire. She was last seen alive in the company of a respectable, educated man, also on a bicycle — one that was painted a distinctive pea green. Hours later, the woman was found dead from a single gunshot wound, and her companion had vanished. The case would trigger a nationwide manhunt, a dramatic discovery in the murky depths of a canal, and a sensational trial that hinged on one question: Was the man on the green bicycle a cold-blooded killer, or the unluckiest man in England?

The summer of 1919 was a summer of absences. In the villages of Leicestershire, as in every corner of Britain, the void left by the Great War was a quiet, constant presence. The men who did return were changed, carrying their own invisible wounds back from the mud of Flanders to the green fields of home. A fragile peace had settled over the land, a peace that felt both welcome and profoundly uneasy. Life, however, had to go on. The rhythms of the countryside were reasserting themselves: the drone of a late-summer bee, the slow drift of clouds, the familiar creak of a bicycle chain on a dusty country lane.

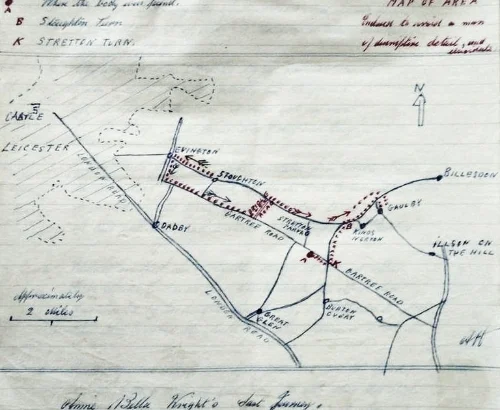

One of those lanes is the Gartree Road. It's an old road, an ancient thoroughfare that has seen Roman legions, medieval pilgrims, and the slow march of centuries. By July 1919, it was a quiet, undulating track connecting small, peaceful villages. It was a place for a quiet walk, a contemplative journey. A place where nothing of note was ever expected to happen.

On the evening of Saturday, 5th July, a local farmer was walking this road, his boots kicking up dust in the failing light. He was heading from Great Glen towards his home in Little Stretton. Just as twilight began to set in, he saw something out of place. There, by a white sheep-gate set into the hedgerow, was a bicycle. And on the grassy verge beside it lay the still figure of a young woman. He called out. There was no answer. He assumed, as anyone would, that he had stumbled upon a simple, tragic accident. A fall. A fatal blow to the head. He was wrong.

The young woman was 21-year-old Annie Bella Wright, and her death on that lonely stretch of road would become one of Britain's most baffling and enduring mysteries, a story not of a simple accident, but of a secret encounter, a fatal gunshot, and a ghost of a man who seemed to vanish into thin air — a man on a green bicycle.

Annie Bella Wright, known to everyone as Bella, was a product of her time. She was born in the final years of the Victorian era, but came of age in the shadow of a world war that had upended old certainties. She lived with her mother and father in the small, close-knit village of Stoughton. Like many young women, she had found a new measure of independence working in a factory. She was employed at Bates and Company, a rubber and waterproof garment works in Leicester, a job that gave her a wage and a life beyond the domestic sphere. By all accounts, she was bright, cheerful, and respectable. She was, in the words of those who knew her, a good girl, but one with a quiet streak of determination. An ordinary young woman looking forward to an ordinary life, in a world struggling to be ordinary again.

In the afternoon of that Saturday, 5th July, Bella made a decision that would seal her fate. She left her mother's house in Stoughton to post a letter to her fiance, Archie Ward, who was stationed with the Royal Navy in Portsmouth, having recently returned from the war. After dropping the letter in the postbox, she mounted her bicycle and set off for the nearby village of Gaulby to see her uncle, George Measures. But she would not make this journey alone. By chance, at around 6:45 PM, as she rode towards Gaulby, she met a man — respectable-looking, perhaps in his mid-thirties, and riding an upright, strikingly green bicycle. Learning of her destination, the man offered to accompany her, and she accepted.

When the pair arrived at her uncle's smallholding, the man waited outside. But George Measures had an uncomfortable feeling about the man his niece had arrived with. Bella explained the situation to him, saying, "Oh him, I don't really know him at all. He's been riding alongside me for a few miles but he isn't bothering me at all." She remarked that he'd behaved like a "perfect stranger". As she prepared to leave, she jokingly told her uncle, "I hope he doesn't get too boring," adding, "I shall try and give him the slip." As Bella left the cottage, the man greeted her: "Bella, you've been a long time. I thought you'd gone the other way." It was about 8:50 PM when they pedalled away from her uncle's cottage together.

But Bella never made it home.

A picture would later emerge from a trail of sightings. From a cottage window near King's Norton, to a crossroads near a village pub, several independent witnesses had seen Bella in the company of the man on the green bicycle, cycling side-by-side, heading towards the loneliest part of the Gartree Road. What did they talk about on that dusty road as the sun dipped below the horizon? Did they share stories of the war, of their lives? Did he charm her with his educated accent? Or did Bella, at some point, feel a flicker of unease? A sense that the man riding beside her was not what he seemed? We can never know. The only two people who knew what happened in those final moments were Bella Wright and the man on the green bicycle — and one of them was now dead.

When the farmer found her at around 9:20 PM, the scene was one of profound and eerie stillness. Bella lay on her back on the grass, her head turned, her hat still on. Her hands were by her sides. There were no signs of a violent struggle, no disarray in her clothing. Just a small wound beneath her left eye, a trickle of blood on her face. Her bicycle was nearby. To the old farmer, it looked for all the world like a terrible, freak accident. He hurried to the nearest farm to raise the alarm.

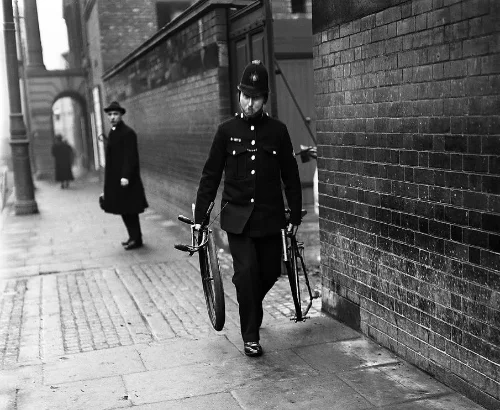

The first official to arrive was the village constable, a man named Alfred Hall. He surveyed the quiet scene under the rising moon. He noted the position of the body, the bicycle resting nearby. He found blood smeared on the top bar of the gate to the field, but could find no footprints on either side of the gate. Soon after, a local physician, Dr Williams, arrived. He conducted a cursory examination there on the roadside. In the dim light, he saw the wound, the blood. He noted some abrasions on her chin. His conclusion was swift and, it seemed, sensible: Bella Wright had likely fallen from her bicycle, striking her head on the hard road or a stone, causing a fatal hemorrhage. He saw no reason to suspect otherwise. Case closed. Accidental Death.

To everyone involved, the sad story of Bella Wright was over, a young life cut short by a tragic mishap. But Constable Hall could not shake a nagging feeling. He was a meticulous man, and something about the scene felt wrong. The way the bicycle was positioned, so neatly. The placid state of the body. The blood on the gate. As the first light of dawn broke over Leicestershire on Sunday, 6th July, the Gartree Road was bathed in a cool, silver glow. While the village of Little Stretton slept, Constable Alfred Hall was already awake. That nagging feeling, the quiet but insistent voice that told him something was wrong with the scene of Bella Wright's death, had not subsided with the darkness. It had sharpened. He returned to the lane at six o'clock in the morning, the dew still heavy on the grass. The doctor had deemed it accidental death, but Hall was now searching for what he truly suspected: signs of foul play. He walked the hedgerow, his eyes scanning every inch of grass, every patch of soil near the white sheep-gate where Bella's body had lain just hours before. He was searching for a clue that the easy explanation had missed.

And then, he saw it. Something small. Something that didn't belong. It wasn't the glint of metal, but rather a small disturbance in the earth. There, pressed into the soft ground by the crescent-shaped imprint of a horse's hoof, was a tiny object, almost completely hidden. He knelt, carefully working it free from the soil. As he wiped the dirt away in the palm of his hand, there was no doubt. It was a bullet, a heavy, lead .455 calibre bullet. He stood up, looking from the small piece of lead in his hand, to the spot, 17 feet away, where Bella's bicycle had been found.

A bullet. This changed everything. The theory of a simple, tragic fall was now collapsing under the weight of this single, damning piece of evidence. With the heavy piece of lead now secure in his pocket, Constable Hall proceeded directly to the building where Bella's body lay. The conclusion of accidental death had been based on the external wound to her face. Hall needed to see it again. There, in the cool stillness of the makeshift mortuary, he took a bowl of water and a cloth. With a professional's resolve, driven by a terrible new certainty, he began to gently wash the congealed blood from the young woman's face. As the skin became clear, the truth revealed itself. It was not a simple cut or a graze from a fall. Beneath her left eye, small and devastatingly neat, was a single, perfectly round hole. An entry wound.

Informed immediately of Hall's grim discoveries — the bullet from the roadside, and the unmistakable wound on the victim — Dr Williams knew a full post-mortem was no longer a formality, it was an urgent necessity. He and another physician would carry it out. Their conclusions were swift, and horrifying. Bella Wright had been shot, once. The bullet had entered beneath her left eye from an estimated distance of six to seven feet. The bullet had passed clean through her head, exiting at the rear of her skull. The official record was now brutally clear. This was not an accident. This was not a fall. This was murder on a lonely country lane. The ghost on the Gartree Road was no longer a chance companion. He was the prime suspect in her murder, and the hunt was on.

The summer of 1919 bled into a cold, damp autumn, and then gave way to the bleakness of winter. The murder of Bella Wright, once a sensational headline that had gripped the nation, began to fade from the pages of the newspapers and from public consciousness. For the Leicester Borough Police, however, the case remained wide open, a source of constant, gnawing frustration. Superintendent Levi Bowley, the meticulous policeman in charge of the investigation, had exhausted every conventional lead. His men had conducted hundreds of interviews, followed up on dozens of false sightings, and meticulously mapped Bella's final journey. But every path led to a dead end. The killer, it seemed, had committed the perfect crime. He had appeared as if from nowhere, and returned to that same void, leaving no name, no motive, and no weapon.

The entire weight of the investigation rested on a single, colorful, and seemingly unobtainable object: the green bicycle. Appeals were made nationwide. Officers visited bicycle manufacturers and repair shops across the Midlands. But no one came forward. The trail was cold. The ghost of the Gartree Road remained a ghost, and the file on Bella Wright gathered dust, a silent monument to a crime that was, for all intents and purposes, unsolvable.

Seven months passed. Then came Monday, 23rd February 1920. The air held the bitter chill of a late English winter. On the River Soar, a man named Enoch Whitehouse was at his work, guiding a horse drawn barge laden with coal along the waterway. It was a slow, mundane, repetitive task he had performed countless times. The horse plodded along the towpath, the heavy rope connecting it to the barge, dipping into the murky, brown water. Suddenly, the rope snagged. It pulled taut, the horse straining against a sudden weight beneath the surface. Mr Whitehouse likely sighed, assuming he'd caught a sunken log or some other piece of river debris. He worked the rope, trying to free it. As he pulled, something heavy broke the surface of the canal with a gurgle of displaced water. It was not a log. It was metal. A strange, skeletal shape, coated in silt and trailing river weeds.

It was the frame of a bicycle.

Enoch Whitehouse knew, as almost everyone in Leicestershire did, about the unsolved murder and the missing clue. He immediately informed the police. The long, cold winter of the investigation was about to come to an abrupt and dramatic end.

Superintendent Bowley seized upon the discovery. This was the first real lead in over half a year. A decision was made to drag that entire section of the canal. Teams of men were dispatched with grappling hooks and chains. It was cold, grim, muddy work. They dredged the canal bed, yard by painstaking yard, their hooks bringing up decades of lost and discarded items.

And then, they started finding things. First, not far from where the frame was snagged, a leather pistol holster. It was empty, but it was military-issue, designed to hold a large-calibre revolver. Hope surged through the search party. A little while later, another find: a small box, rotted by the water but still intact. Inside, cushioned in cotton wool, were bullets — .455 calibre bullets, the same type that had killed Bella Wright. The box was nearly full, only a few rounds were missing. The police now had the killer's discarded kit, a collection of items that told a story of a desperate attempt to erase evidence. But the most important piece was the bicycle frame itself. It was brought back to the police station, where officers began the delicate task of cleaning away seven months of silt and corrosion. As they carefully worked, a small stamped detail emerged from beneath the grime on the head tube. A serial number. This was the key, the key that could finally unlock the entire case.

The serial number became the new focus of the investigation. Bowley's men traced it to the factory where the bicycle was made, and from there to the specific retailer who had sold it, a small cycle shop in Derby. Detectives traveled to the shop, hoping the owner might have some vague recollection. They were met with a stroke of incredible fortune. The shopkeeper was a methodical man who, despite the intervening years of the Great War, still had his old sales ledgers. He turned the dry, brittle pages back to the spring of 1911. And there it was, the serial number matched perfectly. The ledger recorded the sale of one BSA folding bicycle, in green. And next to it, the shopkeeper had written a name. The buyer was a man named Ronald Vivian Light.

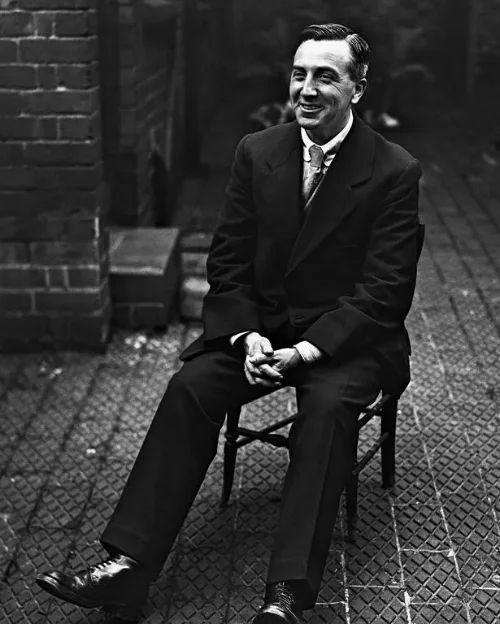

The ghost finally had a name. Police records were checked, and they found him. Ronald Light, 34 years old, living with his mother in a respectable house in Leicester. By all outward appearances, he was the model of a middle-class Englishman. He was a schoolteacher, an ex-officer who had served as a Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers during the war. He was educated, well-spoken. He seemed the furthest thing from a cold blooded killer. But as detectives began to dig deeper into his past, a different, far more disturbing portrait began to emerge, one hidden behind the veneer of respectability. This hidden history was a trail of unsettling incidents and dark accusations. According to a prosecution brief later prepared for the trial, Ronald Light's troubles began early. At the age of 17 he was expelled from the prestigious Oakham School, accused of improper behaviour with younger girls. Similar improper behaviour would continue into his adulthood, according to the brief. Despite this, he was intelligent. He went on to the University of Birmingham, where he graduated as a civil engineer. In November 1906 he secured a respectable job as a draughtsman at the Derby Works of the Midland Railway. For eight years he held this position, but his employment ended abruptly in August 1914, under a cloud of serious suspicion. He was fired, suspected not only of drawing indecent graffiti in a company lavatory, but also of deliberately setting a fire in a cupboard. A whiff of smoke and suspicion seemed to follow him. After being dismissed from the railway, he found employment at a farm. That job also ended with his dismissal, accused of setting fire to haystacks.

So who was Ronald Light? Was he the respectable schoolteacher and war veteran? Or was he a man with a secret history of deviance and pyromania? This was the complex, contradictory figure that the police were now preparing to confront. On the morning of 4th March 1920, Superintendent Bowley walked into the Cheltenham school where Ronald Light had begun working as a mathematics teacher, just two months earlier. He knew he had found the owner of the green bicycle. He was about to come face to face with the man who held the secret of what happened to Bella Wright on that lonely stretch of the Gartree Road.

Ronald Light was taken back to Leicestershire by police. They believed they had their man, but Light was not going to make it easy. Under initial questioning, his denials were absolute. He claimed he hadn't been anywhere near the village of Gaulby on 5th July. He insisted he'd never met a young woman named Bella Wright. When asked about the distinctive green bicycle, he flatly denied ever owning one. But the police had an ace up their sleeve: the bicycle frame, dredged from the canal, with its serial number still legible. When confronted with this, Light's story shifted. Yes, he conceded, he had once owned such a bicycle, but he claimed to have sold it years before to a man whose name he simply couldn't recall.

It was a weak explanation, and it began to crumble as the police tightened the net. One by one, witnesses were brought in for identity parades. Bella's uncle, George Measures, confidently identified Light as the man he had seen waiting for his niece. A local cycle repairman also pointed him out, confirming Light was the owner of the green bicycle he had previously worked on. The most damning testimony, however, came from within Light's own home. His mother's maid informed investigators that on the evening of 5th July, Ronald Light had not returned home until nearly 10 PM. He claimed his bicycle had broken down, forcing him to push it all the way home. She also revealed that he had since sold or destroyed all the clothing he had been wearing that day.

The evidence was overwhelming. The denials, the changing stories, the destroyed clothes. It all painted a picture of a man with something to hide. Finally, faced with the testimony of those who had seen him, Ronald Light's story broke. He admitted it. He was the man on the green bicycle. He had been with Bella Wright. But, he insisted, their encounter was innocent. He claimed they had simply ridden together from her uncle's cottage to the next crossroads, where they amicably parted ways, and he never saw her again. With this new account, the police now had an admission that Ronald Light was with Bella in her final hours, and they charged him with her murder.

The trial of Ronald Light, held in the ancient hall of Leicester Castle in June 1920, was a spectacle. The case had gripped the nation. A real-life murder mystery had played out in the pages of newspapers over the past year, and it was now reaching its dramatic conclusion. The press had largely portrayed Ronald light as an honourable gentleman and a war hero, while casting Bella Wright as a mere factory girl. Some questioned her virtue, in thinly-veiled attempts at victim blaming.

The prosecution, led by the Attorney General Sir Gordon Hewart, was confident. They believed they had a clear, if circumstantial, path to conviction. In his opening, Hewart methodically laid out the case against Ronald Light. He told the jury that at some point on the day of the murder, Bella had fled from Light, the stranger she had politely allowed to accompany her as she cycled to her uncle's home. Perhaps, he suggested, Light's friendliness had turned into unwanted advances, or indecent behaviour. She took a different route home, along the Gartree Road, to avoid him. An angry and frustrated Ronald Light then caught up with her and shot her dead, before fleeing, Hewart told the jury.

He painted a picture of a man whose actions screamed guilt. First, Light was undeniably the man seen with Bella in her final hours. Second, when confronted, he lied repeatedly, denying he was there, denying he owned the bicycle. And third, most damningly, he had systematically disposed of the evidence. He had dismantled the green bicycle and thrown it in a canal, along with his army-issue revolver holster. The bullet that killed Bella, the prosecution argued, was consistent with the .455 calibre ammunition used by that very revolver. For the prosecution, these were the actions of a murderer covering his tracks.

But Ronald Light had his own formidable champion. His defence was led by Sir Edward Marshall Hall, perhaps the most famous and brilliant barrister of his day, known as "The Great Defender". Marshall Hall knew the prosecution's case was strong, but he also knew it was entirely circumstantial — there was no witness to the crime itself. In his opening, he did not contest the basic facts. He stunned the court by admitting Light was with Bella, that he had lied, and that he had hidden the evidence. But, Marshall Hall argued, these were not the actions of a guilty man, but of an innocent one in the grip of sheer panic. He portrayed Light as a timid, nervous man, a former soldier terrified of being wrongly implicated in a terrible crime. Seeing Bella's body, he had simply lost his head and fled, making one foolish decision after another. Marshall Hall's task was to convince the jury that while his client's actions were foolish, they were not murderous.

The prosecution began their case not with the now infamous bicycle, but with Ronald Light's behaviour on that fateful day. They weren't able to introduce Light's history of sexual harassment into evidence, but they still hoped to establish a pattern of unsettling conduct. Their first witnesses to this were two young girls, 14-year-old Muriel Nunney and 12-year-old Valeria Caven. They testified that just three hours before Bella Wright was killed, they had been riding their own bicycles near the very same lonely stretch of road. They claimed Ronald Light had followed and pestered them, making them feel deeply uncomfortable. This testimony was intended to show the jury that Light was not simply a gentleman out for a pleasant ride that day. He was actively seeking the company of young women and girls on bicycles.

The prosecution then moved to its physical evidence. One by one, the items dredged from the canal were presented to the court — the rusted bicycle frame, the water-logged leather of a revolver holster, and a box of .455 calibre bullets. This brought them to the centrepiece of their case: the bullet that killed Bella Wright. Their ballistics expert, Henry Clarke, testified it was consistent with the ammunition for Light's army-issue revolver. This is where Marshall Hall focused his most intense efforts, seeking to prove it could have been something else entirely. He recalled Clarke to the stand.

"Mr Clarke, you are an expert in firearms. You examined the bullet that killed this poor girl. You noted some damage to it, did you not? Damage that may have been caused by a ricochet?" Marshall Hall asked the witness.

"That is correct, sir. There were markings consistent with a possible ricochet," Clarke replied.

"And this bullet, it could be from a rifle as well as a revolver?"

Clarke agreed that it could. The admission, however simple, was a crack in the prosecution's armour. Marshall Hall now began to paint a picture for the jury, an alternative theory of Bella's death:

"So it is possible, is it not, that the fatal shot was fired accidentally, from some distance away, perhaps by a farmer shooting at crows, and that this stray bullet struck the girl? If Miss Wright had been shot at close range by a service revolver, as the prosecution insists, wouldn't it almost blow the side of her head off?"

Clarke responded that it would depend on the velocity. "Of course it does!" Marshall Hall remarked. He let the words hang in the air, having planted the seed of his entire defence. This was not a close-range execution, but a tragic, long-range accident. Death by misadventure.

Then came the defence's biggest gamble. Ronald Light himself took the stand. For five hours, he was subjected to a relentless cross-examination, and his story remained consistent. He began with a startling confession. He readily admitted to having lied to the police upon his arrest. He then admitted to almost everything the witnesses had said. Yes, he was with Bella. Yes, they rode together. But, he insisted, they had parted company peacefully at a junction near King's Norton. His story of what happened next was delivered with a strange, compelling calmness:

"When Bella Wright was murdered, I knew from newspaper reports the next day that she was the girl I had been with just before she died. I knew the police wanted to question me. I became a coward again. I never told a living soul what I knew. I got rid of everything that could have connected me with her because I was afraid. I see now, of course, that I did the wrong thing."

He admitted the holster, the bullets, and the bicycle were all his. He claimed he had disposed of them in a blind panic, terrified by the media consensus that the man on the green bicycle was the killer. Why such panic? He explained he was afraid of worrying his mother:

"She's been under the doctor for many years. She has a bad heart. The shock of my being connected to such a thing, I could not bear the thought of it."

But what about the murder weapon? The prosecution's case depended on him owning that .455 revolver. Here, Light offered an elaborate, detailed, and utterly unverifiable story. He admitted that, as an officer, he had owned a Webley Scott service revolver. However, he claimed that when he was posted overseas to France he had taken the revolver, but not the holster. He testified that in 1918 he became a casualty of war and was sent to a clearing station. In the chaos, he claimed, all of his personal belongings — including the revolver — were left behind, lost forever to the machinery of war. The holster and bullets found in the canal, he explained, were simply spares he had kept at home. It was a perfect story, and because the events had supposedly taken place in a chaotic war zone two years prior, there was no way for the prosecution to disprove it.

In his closing argument, Marshall Hall hammered these points home, painting Light not as a killer, but as a traumatised war veteran — a devoted son who, in a moment of profound panic, made a series of foolish but understandable mistakes:

"Look at the man in the dock. Does he look like a murderer? This is a man who served his country, a man of learning. The Crown says he acted out of guilt. I say he acted out of terror. The terror of an innocent man who sees the net of coincidence closing around him!"

He pointed to the ballistics, and the possibility of a stray bullet. He then attacked the prosecution's speculative theory of the motive for the murder:

"Motive! Where is it? It is the bedrock of any case for murder, and the prosecution has offered you none. They would have you believe that this quiet, respectable man, after a pleasant chat about the scenery, suddenly became a homicidal maniac, produced a pistol, and shot this poor girl, for no reason at all. It is not only improbable, gentlemen, it is incredible. This case is built on a foundation of sand. It is a series of unfortunate events. What the prosecution is asking you to do is to follow the long, pointing finger of coincidence, and hang a man by the neck until he is dead. I ask you to do your duty, and to let this man, this soldier, go free."

But the prosecution, in their closing arguments, had already urged the jury to consider the more obvious explanation for Light's actions:

"Gentlemen of the jury, these are the actions of a man acting from a consciousness of guilt. He takes this bicycle — this critical piece of evidence — he takes it to pieces, and sinks it in the canal. Why? I will tell you why. Because he had murdered the girl."

The jury retired. Ronald Light's life hung in the balance. For just over three hours, the packed courtroom waited in a state of restless suspense. Then, a door opened, and the twelve men of the jury filed back into the box, each man looking grim, their eyes avoiding the prisoner in the dock. A heavy silence fell over Leicester Castle, a crushing weight of anticipation. The Clerk of the Court rose to his feet and put the formal questions to the foreman.

Had they reached a verdict? They had. Then came the final, life-or-death question. Did they find the prisoner, Ronald Vivian Light, guilty or not guilty of the murder of Bella Wright?

Every eye in the room was fixed on the foreman, a middle-aged man whose knuckles were white where he gripped the railing of the jury box. Ronald Light stared at him, his composure finally cracking under the immense strain, his breath held tight in his chest. The foreman cleared his throat, his voice cutting through the silence. The words, when they came, were clear and firm.

"Not Guilty."

Many of the spectators cheered upon hearing the verdict, a sign of the change in public sentiment once the infamous owner of the green bicycle had been revealed to be a well-educated war hero. Ronald Vivian Light, the man at the center of one of Britain's most sensational murder trials, walked free from Leicester Castle. He had faced the gallows and, against all odds, had been spared.

In the aftermath of the trial, life for those involved followed starkly different paths. For Ronald Light, it was the beginning of a second life. For the Wright family, it was the beginning of a long, quiet grief — a grief made heavier by the silence of an unresolved crime. Bella Wright was laid to rest in the churchyard of St Mary and All Saints, in her home village of Stoughton. She was returned to the earth just a short distance from the lanes she knew so well. But the family, working-class people without savings or influence, were left to cope alone. They had lost their daughter, and now they faced the quiet indignity of poverty. They couldn't afford a headstone to mark her final resting place. For more than 60 years, the grave of the young woman at the heart of this national drama lay completely unmarked, known only to her family and a few locals — a patch of anonymous grass in a country churchyard.

Ronald Light, meanwhile, returned to live with his mother in Leicester. But the man who emerged from the trial was not the same one who had entered it. He was a free man, but he was also infamous. He initially maintained a reclusive lifestyle, a man haunted by the shadow of the gallows. He sought anonymity, at one point even assuming the alias Leonard Estelle. But his old habits of deception, it seems, died hard. In December of 1920, just six months after his acquittal, he was fined by the court for registering under that false name at a hotel where he had been staying with a woman. The man who had convinced a jury his panicked deception was a one-time aberration was, it appeared, still a man comfortable with secrets and lies.

For the family of Bella Wright, and for the public, the verdict left not a sense of closure, but a deep, lingering question that would hang in the air for a century: if Ronald Light didn't shoot Bella, who did? Was the theory that Sir Edward Marshall Hall put forward, that had convinced the jury, in fact correct? It's a theory that cannot be disproved. It's entirely possible that on that summer's evening a farmer, a gamekeeper or a poacher fired a rifle some distance away. That the bullet ricocheted, as the expert witness admitted it might have, and by a one-in-a-billion chance found its fatal mark in Bella Wright. Or was Bella murdered, but by somebody else entirely, just a short time after she and Ronald Light had gone their separate ways — a killer who managed to flee the scene without being witnessed? In either scenario, Ronald Light is the unluckiest man in the country, a man whose panicked reaction to a tragedy he wasn't responsible for made him the prime suspect. These are, however, theories wth no evidence.

But was there another explanation, one that was neither a stray bullet from a distant rifleman, nor a cold-blooded murder? For decades, that question remained unanswered. Then a note was unearthed, a secret memorandum, supposedly drafted by none other than Superintendent Bowley himself, the policeman who had hunted Light so relentlessly. The note, if authentic, would change everything. It describes a meeting that took place just three days after Light's acquittal. Light had come to the police station to retrieve the personal items that had been seized from him upon his arrest. Superintendent Bowley wrote that, because he had treated Light well while he was on remand, the two men were on good "terms". He invited Light into his office. It was there, behind a closed door, that the secret was allegedly shared. The note details the conversation that followed.

"If I tell you something, can I depend on you keeping it to yourself?," Light asked. The superintendent assured Light that he could. "Well, I'll tell you, but mind it must be strictly confidential. Nobody else knows about it and if you divulge it I shall, of course, say I never told you anything of the kind."

Then, according to the note, Ronald Light finally confessed. But it was not a confession to murder. It was a confession to a terrible, catastrophic accident.

"I did shoot the girl, but it was completely accidental. We were riding quietly along. I was telling her about the war and my experience in France. I had my revolver in my raincoat pocket and we dismounted for her to look at it. I had fired off some shots in the afternoon for practice and I had no idea there was a loaded cartridge in it. We were both standing up by the sides of our bicycles. I took the revolver from my coat pocket and was in the act of handing it to her. I am not sure whether she actually took hold of it or not, but her hand was out to take it when it went off. She fell and never stirred. I was horror struck. I did not know what to do. I knew she was dead. I did not touch her. I was frightened and altogether unnerved and I got on my bicycle and rode away."

This story, if true, is stunning. It explains everything. It explains his genuine, overwhelming panic. It explains why he would go to such lengths to hide the evidence, not because he was a murderer, but because he was a man responsible for an accidental death, a truth he believed no one would ever accept. It explains the lack of motive, the single shot, the absence of a struggle. It neatly ties up every loose end of the case.

The authenticity of this note, though, is far from certain. Why would Superintendent Bowley, a career policeman, conceal a confession to manslaughter? Why would he not act? Was it a private note, a way for him to mentally close the case he had lost in court? Or is it something else entirely? A later fabrication? We may never know for sure, but the story it tells remains the most compelling, if unproven, solution to the mystery of what happened on the Gartree Road.

Whatever the truth, Ronald Light made the most of his second chance. By 1928 he had left the notoriety of Leicester behind and was living in Leysdown-on-Sea on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent. He had slipped back into the quiet anonymity he seemed to crave. In 1934 he married a widow, Lilian Lester, and settled into a life of quiet domesticity. He, the man at the center of the Green Bicycle Case, simply disappeared from public view. He lived a long, full life. Ronald Vivian Light died on 15th May 1975, at the age of 89. His body was cremated at Charing Crematorium near Ashford, and his ashes were scattered in the crematorium's garden of remembrance. There is no monument to him, just as for so long there was no monument for Bella. He had no children of his own, and in a testament to how completely he buried his past, his stepdaughter had no notion of his infamous trial and acquittal until after his death. The secret, whatever it was, he took with him.

In the 1980s, renewed interest in the case led to a public collection, and a headstone was finally placed on Bella Wright's resting place in Stoughton. It reads: "To the memory of Annie Bella Wright, who was shot and killed in the Gartree Lane, 5th July 1918, aged 21 years. Erected by public subscription."

So we are left with two resting places. One for a young woman whose life was cut short at 21, unmarked for decades because of her family's poverty. The other, the scattered ashes of a man who lived another 55 years after being acquitted of her death. Did the truth die with Ronald Light in 1975? Was it secretly written down in a policeman's controversial note? Or was it something else entirely, a secret that still haunts that lonely, country lane?

More Episodes

The Killing of Maximum John

In May 1979, the American justice system was shaken to its core. Federal Judge John H. Wood Jr. — known by criminals as "Maximum John" for the harsh sentences he handed down — was shot and killed by a sniper outside his San Antonio home. Read more

The Ann Arbor Hospital Murders

In the summer of 1975, panic swept through an Ann Arbor hospital. Patients in the intensive care unit, many recovering well, inexplicably stopped breathing. Doctors and investigators raced to find the cause, realizing this was no medical anomaly — it was murder. Read more