The Ann Arbor Hospital Murders

In the summer of 1975, a wave of unexplained medical crises swept through a veterans' hospital in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Dozens of patients stopped breathing, and the terrifying pattern pointed to murder from within. The desperate investigation that followed would up-end lives, and ignite controversy.

This is the story of a hospital haunted by suspicion, of two immigrant nurses caught in a web of doubt, and of a mystery that still persists today.

Dr Anne Hill had seen thousands of medical emergencies in her time as Chief of Anesthesiology at the Ann Arbor Veterans Administration Hospital. The Irish-born physician had the kind of analytical mind that thrived under pressure. But nothing had prepared her for what would unfold on the afternoon of August 15th, 1975. It was a sweltering summer day in southeastern Michigan, the kind that made the hospital's aging air conditioning system work overtime. The fifth-floor Intensive Care Unit was running at near capacity, filled with patients — men who'd survived the beaches of Normandy, the hills of Korea, and the jungles of Vietnam, only to find themselves fighting different battles, against age, disease, and injury.

At 3:47 PM, the piercing sound of a "Code 7" alarm cut through the afternoon quiet. In room 517, a 64 year-old man had suddenly stopped breathing. His heart continued beating strongly, but his chest had simply stopped its rhythmic rise and fall. The nursing staff rushed to his bedside, but something about the scene struck Dr Hill as profoundly strange. The patient lay completely still, his eyes wide with terror. He was conscious, fully aware, but unable to move a single muscle. It was as if someone had "switched off" his ability to breathe, while leaving everything else intact. Dr Hill had never seen anything quite like it in 20 years of medicine.

23 minutes later, it happened again. Room 519. Another veteran, another set of terrified eyes. The same symptoms: complete respiratory paralysis, strong cardiac function, full consciousness. The staff worked frantically to support his breathing, but Dr Hill's mind was already racing toward a disturbing conclusion.

Then, at 4:32 PM, the impossible became undeniable. A third patient, room 521. The same floor, the same symptoms, the same terrifying precision. Three men in 20 minutes, all with identical respiratory failures that defied medical explanation.

But Dr Hill knew better. Her years of experience with anesthesia had taught her to recognize the effects of neuromuscular blocking agents, drugs like pancuronium bromide, marketed as Pavulon. She'd administered it countless times during surgery, watching as patients' muscles relaxed under its influence. The symptoms were unmistakable. Acting on her medical instincts, Dr Hill quickly administered neostigmine, the antidote used to reverse the effects of Pavulon during surgery. The results were immediate, and dramatic. Within minutes, all three patients began breathing normally again. Their muscle function returned, and the look of terror faded from their eyes.

That evening, Dr Hill made the call that would transform the Ann Arbor VA Hospital into the epicenter of one of the most controversial criminal investigations in American history. She contacted the FBI, convinced that someone was walking the halls of her hospital systematically poisoning veterans with a drug designed to paralyze them into suffocation.

What she didn't know, was that this had happened before. Over the previous six weeks, the hospital had recorded more than 50 similar respiratory emergencies — an enormous statistical anomaly that had somehow escaped official notice, until that terrifying afternoon when three attacks happened in rapid succession.

The hunt for a killer was about to begin.

Within hours of Dr Hill's call, the Ann Arbor Veterans Administration Hospital was transformed into what looked like a military installation under siege. FBI agents descended on the facility with the kind of methodical precision usually reserved for counterintelligence operations, turning the halls of healing into a crime scene of unprecedented complexity. The investigation that followed would eventually consume more than 200 federal agents, and cost taxpayers over $1 million, making it one of the most expensive criminal inquiries in FBI history at that time.

But the scale of the challenge facing investigators was staggering. How do you identify a killer among 750 hospital employees, when the only evidence is a pattern of mysterious deaths that left no traditional forensic clues? Special Agent Delmar Ward, assigned to the FBI's Ann Arbor resident office, took charge of the initial investigation. Ward was an investigator with a background in white-collar crime, but nothing in his training had prepared him for the unique challenges of a hospital serial-poisoning case.

The first priority was establishing the scope of the crimes. Working with hospital administrators and medical records staff, agents began reconstructing every suspicious death and respiratory emergency that had happened since early July. What they found was deeply disturbing — a pattern of attacks so unusual that it suggested either extraordinary medical coincidence, or deliberate, systematic murder. Between July 1st and August 15th, the hospital had recorded 51 "Code 7" respiratory emergencies. Under normal circumstances, they were rare events — perhaps one or two per month in a facility of this size. The sudden spike represented a statistical impossibility that could only be explained by human intervention.

The FBI established a command post within the hospital, interviewing every employee who had access to the Intensive Care Unit during the relevant time periods. The interviews were exhaustive, sometimes lasting six hours or more, as agents probed for any detail that might reveal the identity of the poisoner. The investigation quickly revealed the shocking ease with which someone could commit these crimes. Pavulon was stored in an unlocked refrigerator in the ICU nursing station, accessible to doctors, nurses, orderlies, and even visitors who might wander into the area unobserved. The drug was so freely available that partly filled vials could be found discarded in hospital waste baskets, having been used for legitimate medical reasons and then carelessly disposed of. Hospital security was virtually nonexistent, by modern standards. There were no ID badges required for staff, no sign-in procedures for visitors, and no surveillance cameras in critical areas. The hospital operated more like a college campus than a secure medical facility, with people moving freely between floors and departments without challenge.

As the investigation progressed, agents began focusing on the timing of the attacks. Pavulon acts within three minutes of injection. This meant that whoever administered the drug had to be in close proximity to the victim immediately before the onset of symptoms. Working backward from each respiratory emergency, investigators created detailed timelines showing which hospital staff members had been present in the relevant areas during the critical three-minute windows. The process was painstakingly slow, requiring agents to cross-reference work schedules, patient assignments, and witness statements, for dozens of separate incidents.

Two names began appearing with disturbing frequency on these timelines: Filipina Narciso and Leonora Perez. Both were experienced ICU nurses who worked the afternoon shift, the shift when most of the suspicious respiratory failures had happened. Both had access to Pavulon, and the medical knowledge to administer it effectively. But correlation was not causation, and FBI investigators knew they needed more than statistical coincidence to build a criminal case. They needed witnesses, physical evidence, or confessions. What they got instead was a complex web of circumstantial evidence, questionable witness testimony, and investigative techniques that would later be condemned by the courts as fundamentally flawed. The investigation was about to take several controversial turns that would transform a search for justice into a cautionary tale about the dangers of tunnel vision and the vulnerability of immigrant communities.

August 16th, 1975. Less than 24 hours after the FBI had been called into the Ann Arbor VA Hospital, Agent Delmar Ward found himself standing at the bedside of John McCrery, a 50-year-old heart patient from Coloma, Michigan, who had nearly died the previous evening. McCrery was alive, but he couldn't speak. A breathing tube inserted during his resuscitation left him able to communicate only through head movements and written notes. What happened next would become one of the most controversial pieces of evidence in the entire case: an impromptu bedside identification that violated virtually every protocol for proper police lineups, yet would serve as a cornerstone of the prosecution's case against Filipina Narciso.

McCrery had been found in respiratory distress around 8:30 PM on August 15th, about one hour before the third and final attack that had prompted Dr Hill to call the FBI. When he was revived, hospital staff asked if he could remember anything about the person who'd been in his room before he stopped breathing. Unable to speak, McCrery had scrawled a cryptic three-letter note: "P.I.A.". To hospital administrators, the meaning seemed obvious. Filipina Narciso was known around the hospital by the nickname "P.I." The connection, they thought, appeared straightforward: McCrery was identifying his attacker by name. Investigators, and later prosecutors, never offered a clear or consistent explanation for the added letter. It may have seemed a small detail to them at the time, but that unexplained letter would become one of many cracks in the government's case early signs that what appeared straightforward might, under closer scrutiny, prove far more uncertain.

Agent Ward, working with hospital administrator Gary Calhoun, devised what they believed was a simple test of McCrery's identification. Three nurses would be called to McCrery's bedside, one by one, and asked to explain how the intravenous tubes were connected to his body. After each nurse left, McCrery would be asked whether she was the person who had given him the injection that nearly killed him.

The first nurse approached McCrery's bed, and carefully explained the IV setup. After she left, Ward asked McCrery if she was his attacker. McCrery shook his head, no. The second nurse repeated the process, with the same result, a definitive shake of the head indicating no. Then Filipina Narciso entered the room. She was 30 years old, barely five feet tall, with the kind of gentle demeanor that had made her popular with patients throughout her three years at the hospital. Unaware that she was participating in what amounted to a police lineup, Narciso carefully and professionally explained McCrery's IV system, showing the same attention to detail that had earned her recognition as a superior nurse. When Narciso left the room, Agent Ward posed the crucial question. "Is she the one who gave you the injection?" According to Ward's testimony, McCrery nodded his head once — a single, deliberate movement that would help seal Narciso's fate.

But even as Ward was documenting what he believed was a clear identification, the evidence was already beginning to unravel. Other witnesses had reported that McCrery had described his attacker very differently — as a man, possibly of Mexican or Puerto Rican descent. Some staff members recalled him making gestures suggesting his attacker had been taller and heavier than the petite Filipino nurse. More troubling still was McCrery's mental state. The respiratory arrest had deprived his brain of oxygen for several critical minutes, and the subsequent open-heart surgery he underwent just days later would result in what doctors diagnosed as retrograde amnesia — a complete loss of memory surrounding the traumatic events. Within a week of the bedside line-up, McCrery could no longer remember Agent Ward, the nurses who'd visited his room, or writing the "P.I.A." note. When questioned again, he insisted he had no recollection of the attack whatsoever.

The investigation had barely begun, and already its first major piece of evidence was compromised. But rather than reconsidering their approach, FBI agents pressed forward, convinced they were on the right track. They had no way of knowing that their key witness would be dead within a year, taking any possibility of clarification to his grave. John McCrery died in June 1976, of a heart attack, while mowing the lawn at his home in Coloma. He was 51 years old. His death would deprive both the prosecution, and the defense, of the chance to question him further about the events that had nearly claimed his life. The bedside lineup that had seemed so promising to investigators would become a permanent source of controversy, a piece of evidence that raised more questions than it answered. The FBI's case, it seemed, was built on shifting sand.

If the McCrery identification was problematic, the testimony of Richard Neely represented something far more troubling: the use of experimental psychological techniques to extract memories that may never have existed in the first place. Neely was a 62 year-old retired factory worker from Osceola, Indiana, who had been admitted to the Ann Arbor VA Hospital for treatment of bladder cancer. On the evening of July 30th 1975, he experienced a sudden respiratory arrest that nearly killed him. When he recovered, Neely insisted he had no memory of the attack whatsoever. For FBI investigators, Neely represented a potentially crucial witness. Unlike McCrery, he'd had no subsequent medical procedures that might have affected his memory. If they could somehow unlock his recollections of the attack, he might be able to identify his attacker, and provide the breakthrough the investigation desperately needed.

Enter Dr Herbert Spiegel, a New York psychiatrist and pioneer in the use of hypnosis for criminal investigations. In the mid-1970s, law enforcement agencies across the country were experimenting with hypnosis techniques to help witnesses recover suppressed memories. The Los Angeles Police Department had even created so-called "Svengali Squads" dedicated to hypnotic interrogation. But the science behind hypnotically recovered memory was highly questionable, even by 1970s standards. Critics argued that subjects under hypnosis were highly susceptible to suggestion, and might construct detailed false memories based on leading questions or subtle cues from interrogators.

Over the course of three separate sessions, Dr Spiegel placed Neely in hypnotic trances while FBI agents questioned him about the evening of July 30th. The sessions were conducted with agents firing questions at the hypnotized patient, while Spiegel monitored his psychological state. Initially, Neely's hypnotically induced testimony was contradictory and confusing. In one session, he described his attacker as a "stocky black man". In another, he implicated a different nurse entirely. But gradually, under persistent questioning, a more focused narrative began to emerge. By the third session, Neely was identifying Leonora Perez as the nurse who had been in his room shortly before his respiratory arrest. The identification, by the end, seemed clear and definitive, exactly what the FBI needed to move forward with their case. But like McCrery, Neely wouldn't live to see the resolution of the case. He died of complications from his cancer before the trial ended, taking with him any possibility of knowing whether his identification of Perez was based on true memory, or hypnotically implanted suggestion. The FBI's second key witness had been as compromised as the first, leaving the prosecution's case dependent on evidence that was becoming increasingly questionable with each passing month.

While the FBI was focusing its investigation on Filipina Narciso and Leonora Perez, a disturbing story was unfolding just a few miles away, at the University of Michigan Neuropsychiatric Institute. There, a 51-year-old nursing supervisor named Betty Jakim was undergoing treatment for severe depression, feelings of guilt, and hallucinations, that would ultimately lead to one of the most explosive revelations in the entire case. Jakim had been the evening shift supervisor in the intensive care unit during the summer of 1975, working directly with both Narciso and Perez during the period when the mysterious respiratory arrests were happening. She was one of the first people investigated by the FBI, but was quickly eliminated as a suspect when agents determined she hadn't been present during many of the most suspicious attacks. What the FBI didn't know — or chose not to pursue — was that Jakim was suffering from terminal cancer and taking powerful medications that were causing severe mood swings and psychological disturbances.

In early 1976, Jakim voluntarily committed herself to the University of Michigan Neuropsychiatric Institute, seeking treatment for what she described as overwhelming feelings of guilt and responsibility for the deaths at the VA hospital. During her psychiatric treatment, she made a series of stunning admissions that should have transformed the entire investigation. According to sources familiar with her psychiatric records, Jakim repeatedly confessed to psychiatrists that she was responsible for the patient deaths and poisonings, insisting that Narciso and Perez were completely innocent. But the psychiatrists treating Jakim never reported her confessions to authorities. They believed, according to later testimony, that her statements stemmed from her deteriorating mental state, and the powerful medications she was taking for her cancer treatment.

But the revelation came too late for a proper investigation of Jakim's role in the case. On February 3rd, just weeks before the nurses' trial was to begin, Betty Jakim died in Sebring, Florida, having taken an overdose. Jakim left behind what some sources described as a suicide note, in which she again insisted on the innocence of the two Filipino nurses. But like so much other evidence in the case, the note would become a source of controversy rather than clarity. Federal prosecutors questioned its authenticity and relevance, arguing that Jakim's mental state had been too compromised for her statements to be considered reliable.

Van Dam announced that the FBI would look into Jakim's possible link to the murders, but this appeared to be more of a public relations gesture, as agents seemed to double down on their case against Narciso and Perez. Defense attorneys would later argue that Jakim's suicide and confessions represented the most important evidence in the entire case — proof that the real perpetrator had been overlooked, while two innocent nurses were scapegoated for crimes they didn't commit. But with Jakim dead, and her psychiatric records sealed, the truth about her role in the VA hospital murders would remain forever elusive.

The investigation that had begun with such promise was becoming a study in tunnel vision, prosecutorial misconduct, and the dangers of allowing bias and prejudice to shape the pursuit of justice.

To understand the full horror of what happened at the Ann Arbor VA Hospital, you first have to understand the weapon used in these attacks: pancuronium bromide, or Pavulon. A drug that represents one of modern medicine's most elegant solutions to a surgical problem, and one of the most terrifying substances ever used to commit murder. Pavulon belongs to a class of medications known as "neuromuscular blocking agents", a molecule engineered to interact with specific receptors in the human nervous system, with devastating efficiency. The drug works by blocking the transmission of nerve impulses, causing progressive paralysis that spreads throughout the body within minutes. In a surgical setting, this paralysis is precisely controlled and carefully monitored. Patients are first rendered unconscious with anesthetic agents, then given Pavulon to relax their muscles, during complex procedures. Mechanical ventilators take over the work of breathing, while anesthesiologists monitor every vital sign to ensure patient safety. When surgery is complete, antidotes like neostigmine reverse the drug's effects, allowing normal muscle function to return.

But when administered outside of this controlled environment, Pavulon becomes an instrument of torture. The drug affects muscles throughout the body, including the diaphragm and intercostal muscles essential for breathing, while leaving the heart and brain completely unaffected. Victims remain fully conscious and aware, as their ability to breathe slowly disappears. Death occurs within minutes, unless the victim receives immediate mechanical ventilation, or an antidote to reverse the drug's effects. The process was described by one medical expert as "pharmacological drowning" — the victim suffocates, while remaining completely alert and aware.

The forensic challenges posed by Pavulon were unprecedented in 1975. Unlike traditional poisons that leave obvious traces in blood or tissue, Pavulon metabolizes rapidly and disappears from the body within hours. Standard autopsy procedures would reveal no obvious cause of death, making these murders nearly perfect crimes from a forensic perspective. FBI forensic scientists had to develop entirely new techniques to detect Pavulon in tissue samples from deceased victims. Working with pharmaceutical companies and university researchers, they created specialized chemical assays that could identify microscopic traces of the drug in liver and kidney tissue. The process was painstakingly complex, and the tests could only detect Pavulon if performed within a short window after death, further complicating the investigation of the earlier suspicious deaths.

Dr Anne Hill's decision to test for Pavulon on August 15th represented a crucial breakthrough in the case. Her background in anesthesiology allowed her to recognize the symptoms and give the appropriate antidote, saving three lives, and provided the first concrete evidence that deliberate poisoning was happening.

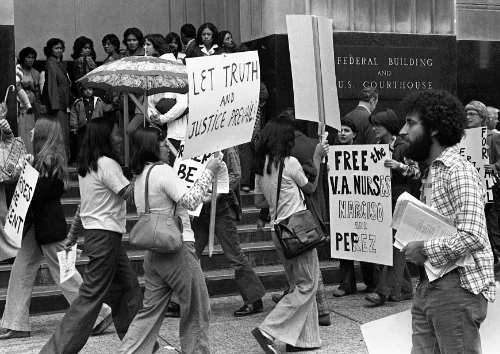

From the moment Filipina Narciso and Leonora Perez were arrested, the Ann Arbor Hospital murders case became something far more than a criminal investigation. It transformed into a cultural battlefield, where issues of race, immigration, and American identity collided with questions of justice and fairness. The mid-1970s was a time of significant social tension in the United States. The country was still reeling from the Vietnam War, grappling with economic recession, and experiencing rising anxiety about Asian immigration after the passage of the 1965 Immigration Act. Filipino nurses, despite their crucial role in American health care, found themselves caught in the crosscurrents of these tensions. For many in the Filipino-American community, the prosecution felt like a modern day witch hunt, an attempt to scapegoat convenient foreign suspects for crimes the system couldn't solve.

The timing was particularly sensitive, as the case unfolded during a time of increased anti-Asian sentiment, and growing tensions between the United States and the Philippines under Ferdinand Marcos's increasingly authoritarian rule. The racial undertones of the investigation became explicit during the FBI's interviews with hospital staff. Some witnesses, who'd once been friendly colleagues, now testified about the nurses' supposedly strange behavior, or claimed they'd seen them acting suspiciously near patients' rooms.

The case also highlighted tensions within the healthcare system about the role of foreign-trained medical staff. Some American nurses and nursing organizations had expressed concerns about the rapid influx of Filipino nurses, arguing that it depressed wages and working conditions for domestic nurses. These tensions created an environment where Filipino nurses faced heightened scrutiny and suspicion, even from colleagues who might otherwise have been supportive. Filipino communities across the U.S. organized support campaigns, seeing the case as a test of whether immigrants could receive equal justice in the American legal system. The case became a symbol of the immigrant experience in America, the tension between seeking opportunity and remaining forever vulnerable to suspicion and scapegoating.

On March 1st 1977, the most complex and controversial criminal trial in Michigan federal court history began in downtown Detroit. The case would consume 13 weeks and feature more than 100 witnesses. The jury selection process alone took several weeks, highlighting the tensions surrounding the case. Potential jurors were questioned about their military service, their attitudes toward government authority, and whether they had, in the words of the court, "ever heard anyone speak in a derogatory manner about Filipinos or Asians".

The prosecution team, led by Assistant U.S. Attorneys Richard Yanko and Richard Delonis, faced the challenging task of building a murder case based entirely on circumstantial evidence. In his opening statement, Yanko acknowledged that the government had no "smoking gun". But he argued that the cumulative weight of circumstantial evidence would prove the defendants' guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Their strategy centered on establishing opportunity and access. They planned to show that Narciso and Perez had been present near the victims during the critical time periods when the Pavulon must have been administered, and that both nurses had the medical knowledge and hospital access needed to commit the crimes.

The defense team focused on highlighting the weakness of the government's evidence, the flawed investigative techniques used by the FBI, and the cultural bias that had influenced the entire case.

The trial's early weeks were dominated by medical testimony about the effects of Pavulon, and the methods used to detect it in tissue samples. The timing of Pavulonn's effects had been crucial to the investigation. The prosecution called expert witnesses who explained that the drug causes complete respiratory paralysis within three minutes of injection. This narrow window, the prosecution argued, meant that whoever administered the poison had to be in close proximity to the victim immediately before the symptoms began. But the prosecution's medical experts disagreed about some crucial details. Dr Marcelle Willock testified that, under certain conditions, Pavulon could be effective if injected into an IV bag, rather than directly into the intravenous line, potentially causing breathing failure 10 to 15 minutes, or even hours, after injection. This "time bomb" theory seriously undermined the prosecution's timeline-based case against Narciso and Perez. If Pavulon could cause delayed effects, then the poisoner could have been long gone by the time victims collapsed, making the FBI's careful reconstruction of who was present during the critical three-minute windows largely irrelevant.

The scientific evidence, which should have been the foundation of the prosecution's case, instead became another source of controversy and confusion. Expert witnesses disagreed about dosages, timing, and methods of administration, leaving jurors to navigate complex medical testimony that failed to provide clarity.

The testimony of surviving victims provided some of the trial's most dramatic moments. Those who'd experienced the respiratory attacks described the terrifying sensation of being completely paralyzed while remaining fully conscious, a nightmare scenario that underscored the cruelty of the crimes.

But the prosecution's key witness testimony proved deeply problematic so much so that the two central pillars of the government's case spectacularly crumbled before the jury ever heard them. The controversial bedside identification by John McCrery, which the FBI had built its early case around, was ultimately excluded by the judge. He ruled the cryptic "P.I.A." note was far too ambiguous to definitively identify Narciso. The defense, however, had uncovered even more devastating flaws: testimony revealed McCrery had told another nurse his attacker was a "Mexican female" and, when asked directly if Narciso was the assailant, had replied "no." Even more shocking, FBI witnesses were forced to testify that McCrery had twice identified a different woman from photos as the person he meant by "P.I.A." — a woman who was then granted immunity in exchange for testifying against the nurses.

The Richard Neely hypnosis evidence fared no better. While the defense challenged the reliability of hypnotically-induced memories, they also exposed Neely's profound prejudice. A court-ordered psychiatrist, Dr. Dennis Walsh, testified that Neely harbored a "very paranoid" belief in a nationwide conspiracy of 1,800 Filipino nurses trying to kill Americans, and another witness testified Neely had used a racial slur to describe the nurses. Faced with this, the prosecution dropped Neely from the list of victims Perez was charged with poisoning, ensuring his identification was never presented in court.

Of all the dramatic moments in the trial, none was more explosive than the testimony of Julie Porter. She was a licensed practical nurse who had worked alongside Narciso and Perez in the Intensive Care Unit during the summer of 1975. Porter's appearance on the witness stand would raise troubling questions about whether federal agents had deliberately excluded potential suspects from their inquiry. She'd been called as a prosecution witness, but her testimony quickly went off script in ways that clearly surprised and alarmed the government attorneys. Speaking in a clear, determined voice, Porter described what she characterized as "four hours of FBI interrogation and harassment" that had taken place on September 11th 1975, less than a month after the federal investigation began.

The FBI agents who'd questioned her were looking for any information that might help them identify the poisoner among the afternoon shift staff in the Intensive Care Unit. But according to Porter, the agents had made it clear from the beginning that they were only interested in certain categories of suspects. "I asked why it had to be someone on afternoons," she testified, referring to the agents' apparent focus on the afternoon nursing shift where most of the suspicious respiratory failures had happened. The agent's response, according to Porter, was chilling. "He said it was because he had orders that Dr Lindenauer didn't want his doctors harassed".

Dr S. Martin Lindenauer was the hospital's Chief of Staff, a respected physician who'd been on a European sabbatical when the mysterious deaths began in July 1975. According to Porter's account, FBI agents had been instructed not to investigate doctors or medical students in connection with the poisonings, effectively limiting their inquiry primarily to nursing staff. If true, it meant that the FBI had artificially narrowed their investigation from the very beginning, potentially allowing the real perpetrator to escape scrutiny, while focusing exclusively on nurses like Narciso and Perez.

Defense attorneys overcame heated prosecution objections to have Porter describe her FBI interrogation in detail. She testified that agents had used aggressive tactics, essentially telling her that one of the five afternoon shift nurses had to be responsible for the crimes. "One of them held up his hand and started counting," Porter recalled. "He said 'there are five of you in the ICU. Lula Balls didn't do it, Bonnie Bates didn't do it, and you say you didn't do it. Now, who does that leave?' I told him it doesn't leave anybody because Perez and Narciso didn't do it either".

The prosecution's case was damaged even more when Porter revealed more about the hospital's chaotic situation. She described an environment where understaffing and poor supervision had created many opportunities for unauthorized people to access sensitive areas, including the Intensive Care Unit where the Pavulon was stored. She also described a disturbing incident that had happened at the time of one of the suspicious deaths. She described how a mentally disturbed patient named Dan Warren, who was supposed to be restrained to his bed, had been found standing in the room of John Herman shortly after Herman had stopped breathing. Warren was described as a schizophrenic patient who suffered from disorientation and occasionally catatonic episodes. Despite being considered potentially dangerous if unsupervised, Warren had somehow freed himself from his restraints and wandered into Herman's room undetected. When Porter discovered the scene, Warren was standing silently near Herman's bed while the veteran lay dying. The defense seized on this to argue that the hospital's security was so lax that virtually anyone could have committed the crimes. If a mentally ill patient could wander freely into other patients' rooms without detection, how could the prosecution argue that only the afternoon nursing staff had access to potential victims?

Dr Lindenauer, when contacted by reporters after Porter's testimony, denied that he'd ever instructed FBI agents to avoid investigating doctors or medical students. And FBI agents at the scene also denied Porter's account, insisting that they'd never been given orders to limit their investigation to nursing staff. But the damage to the prosecution's case was significant.

As the trial continued, one glaring problem remained: motive. Why would two dedicated, well-regarded nurses embark on a systematic campaign to murder the very patients they had sworn to protect? The prosecution would eventually present a theory that Narciso and Perez had poisoned patients not to kill them, but to create medical emergencies that would show how understaffed and overworked the intensive care unit had become. The staffing situation at the Ann Arbor VA Hospital in the summer of 1975 was, indeed, problematic. The facility was experiencing the kind of budget constraints and personnel shortages that plagued many VA hospitals at the time. In the Intensive Care Unit nurses were responsible for large numbers of patients, and the demanding critical care work was taking its toll on staff morale.

According to this theory, the nurses had developed a scheme to artificially create respiratory emergencies that would show the need for extra staffing and resources. They allegedly believed that by causing non-fatal attacks, they could force the hospital to provide better working conditions for the nursing staff. But this theory was problematic. If the nurses didn't want their victims to die, why had they used a drug as dangerous and fast-acting as Pavulon? Why had they continued the attacks even after several patients had died? And why had they made no effort to ensure that medical help was immediately available for all of their victims? The theory required the jury to believe that two professional nurses would risk their careers, their freedom, and their patients' lives to make a point about hospital management. The risk-to-benefit ratio was wildly disproportionate.

As the trial moved into its final weeks, both sides prepared for closing arguments that would try to distill weeks of complex and often contradictory testimony. Prosecutor Richard Yanko delivered a seven hour summation that attempted to weave together all the circumstantial evidence into a coherent narrative of guilt, telling the jury that "the mystery of this whole incredible, mad, senseless scheme is solved when one realizes that they did not want their victims to die". He suggested that the nurses had set up a system to ensure that poisoned patients would be discovered and revived before suffering permanent harm.

Defense attorney Thomas O'Brien's closing argument was equally passionate. He characterized the prosecution as a misguided attempt to find someone to blame for tragic events that might have had entirely different explanations.

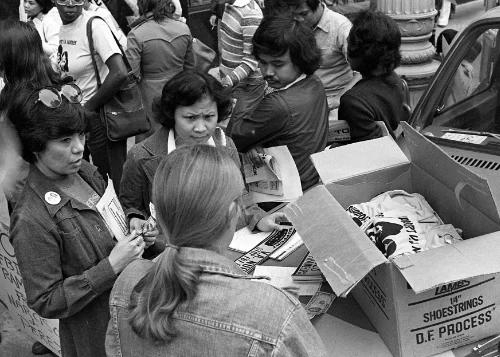

After 13 weeks of testimony, the case went to the jury for what would become one of the longest deliberations in federal court history. They would spend 94 hours, across 13 days, wrestling with the complex evidence — trying to determine whether two Filipino nurses were guilty of multiple murders, or whether they were innocent victims of a flawed investigation. The jury deliberations began on June 30th, in a federal courthouse that had become the focal point of international attention. Outside, Filipino-American protesters maintained a vigil, holding signs proclaiming the nurses' innocence. Inside, 12 citizens weighed evidence that was both vast and problematic.

The immediate reaction to the verdict was one of shock and disbelief. Two alternate jurors expressed amazement at the guilty findings. "I just cannot imagine how anyone could return a verdict like that," one told reporters. Even some prosecution staff privately expressed surprise at the convictions — they expected acquittals, based on the weakness of the evidence and the problems that had emerged during the trial. The Filipino-American community reacted with outrage and despair. Community leaders denounced the verdict as the product of racial bias and prosecutorial misconduct. The defense immediately announced their intention to appeal. The legal battle was far from over.

The appeal process would uncover even more disturbing evidence of misconduct and investigative flaws. The defense detailed a pattern of prosecutorial overreach that was stunning. Prosecutors were found to have withheld favorable evidence from the defense — a tactic the judge angrily compared to a "game of five card stud poker" rather than a search for the truth. They had also altered FBI reports that were supposed to be turned over in their entirety, and had sent a letter to witnesses warning them to be cautious in dealing with the defense, which the judge described as "improper and ill-advised". The misconduct extended into the courtroom and the press. Prosecutor Richard Yanko had made public statements declaring the nurses guilty "whether they are convicted or not" — a severe violation of Bar Association rules. During the trial, he had improperly cross-examined Narciso by repeatedly asking if she thought other witnesses were lying, implying that any differences in the testimony could only be the result of her or the other witness committing perjury. Later, he wrongly implied to the jury that the defense had a duty to prove their clients' innocence. These revelations, combined with the judge's own acknowledgment that the government had presented "no direct proof" of guilt, proved devastating.

In December 1977, Judge Philip Pratt — the same judge who had presided over the original trial — ordered a new trial for both defendants. He would say that, "the insidious accretion of prosecutorial misconduct had polluted the waters of justice". He noted that while no single instance of misconduct was enough for a reversal, the combined effect was devastating to the fairness of the trial. Faced with judicial condemnation of their conduct, and the prospect of retrying a case that had already been severely criticized, federal prosecutors made a pragmatic decision. On February 1st 1978, U.S. Attorney James Robinson announced that all charges against Narciso and Perez were being dropped. He said that it was unlikely prosecutors could obtain guilty verdicts in a second trial, effectively ending one of the most controversial prosecutions in federal court history. For Filipina Narciso and Leonora Perez, the dropped charges were vindication after more than two years of legal nightmares. "It's the first good Christmas in two years," Narciso told reporters. Four months later both nurses returned to the Philippines, their American dreams forever soured by their experience with the U.S. justice system.

Five decades have passed since that terrible summer of 1975. The healthcare security revolution that followed has undoubtedly saved lives by making it much more difficult for criminals to harm patients in hospital settings. Modern healthcare facilities have sophisticated security systems that would have prevented the kind of access and opportunity that made the 1975 crimes possible. The investigative techniques criticized in the case have largely been abandoned or significantly reformed. The use of hypnosis to recover witness testimony has been severely restricted by courts across the country, with many jurisdictions now prohibiting such evidence entirely. Forensic science has also advanced dramatically since 1975. The kind of toxicological testing that took weeks or months to complete during the original investigation can now be performed in hours or days, making it much easier to identify poison cases and link them to specific perpetrators.

The treatment of Filipina Narciso and Leonora Perez still resonates today, in debates about immigration, multiculturalism, and the place of newcomers in American society. Their experience illustrates how quickly acceptance can turn to suspicion, and how the American dream can become a nightmare when fear and prejudice threaten to overwhelm reason and fairness.

In the end, the Ann Arbor Veterans Administration Hospital murders remain one of America's most significant unsolved criminal cases. Despite years of investigation, months of trial testimony, and decades of scrutiny, the fundamental questions remain unanswered. Who killed the patients? Why were they targeted? And was justice ultimately served? Whether Narciso and Perez were guilty or innocent, whether Betty Jakim was the real perpetrator or another victim of the system's failures, the ten veterans who died that summer were gone forever — their final chapter written in confusion and controversy, rather than dignity.

More Episodes

The Vanishing of John Ruffo

In 1998, John Ruffo, a charismatic New York businessman, was due to begin a 17-year sentence for an audacious $350 million bank fraud. He drove to an ATM, withdrew a few hundred dollars, abandoned his car at JFK airport, and simply vanished. Read more

The Man in Room 1046

In 1935, a man with no luggage, using a fake name, was found tortured inside a locked room at the Hotel President in Kansas City. His last words were a lie, and the police had no weapon, no suspects, and no motive. Read more