The Vanishing of John Ruffo

In 1998, John Ruffo, a charismatic New York businessman, was due to begin a 17-year sentence for a staggering $350 million bank fraud. He drove to an ATM, withdrew a few hundred dollars, abandoned his car at JFK airport, and simply vanished.

This episode dives into the story of one of America's most audacious scams and one of its most elusive fugitives. We uncover how Ruffo and his partner, Edward Reiners, conned international banks with a fictitious tech project, and then explore the decades-long manhunt that followed Ruffo's disappearance.

John Ruffo was an ordinary man, with an extraordinary talent for deception. A computer expert with a knack for storytelling, he crafted a fraud so elaborate it fooled some of the biggest banks in the world, and stole $350 million in the process. Then, just days before he was supposed to begin a 17-year federal prison sentence, he vanished leaving no trace. More than two decades later, Ruffo remains one of the FBI's most-wanted white collar fugitives.

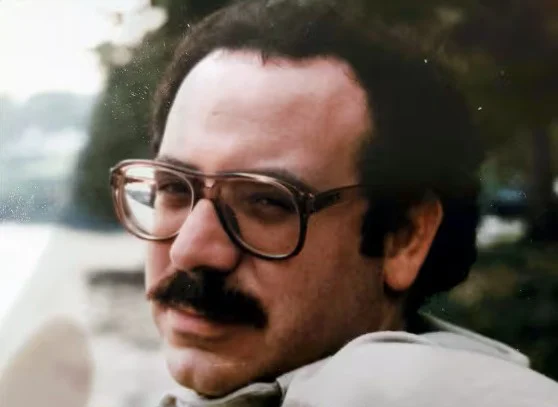

Let's start with the basics. John Ruffo wasn't what you'd call flashy. He lived in Brooklyn, he enjoyed working with computers, he was married to Linda. They had a seemingly ordinary suburban life. But there was one thing about John Ruffo that wasn't ordinary: he was a born storyteller, and he was very, very good at it. He ran a small business, a computer resale company called Consolidated Computer Services, or CCS. It was a legitimate supplier of tech systems, at least to begin with — an IBM reseller.

Some time in 1992, Ruffo partnered with an old acquaintance, Edward Reiners. Reiners had once been a senior executive at Philip Morris, one of the largest tobacco companies in the world. He likely first crossed paths with Ruffo when CCS supplied computers to the tobacco company. When Reiners joined forces with Ruffo after being let go from Philip Morris, he provided the credibility that would be needed for the pair's new venture. Together Reiners and Ruffo came up with a scheme that, in its audacity, is almost beautiful.

Here's how they executed it.

Ed Reiners, slick and confident, walks into a computer leasing company called Nelco. But he's not just any businessman. He's posing as a top executive from Philip Morris. He claims to be the Chief Operating Officer of something called "Project Star" — a hush-hush operation supposedly researching the long-term effects of smoking, and developing a "smokeless" cigarette. Reiners spins a tale of secret laboratories hidden away in Central America, Asia and Europe — five covert research sites that all need cutting-edge computer equipment to keep the project running.

But here's the catch: the entire thing must stay under wraps. Total secrecy. No leaks.

So, he asks Nelco for help. Nelco is supposed to acquire and finance massive amounts of high-tech computer equipment for this mysterious Project Star. Sounds impressive, right? Together with Nelco, he convinces several banks to loan millions to buy these computers from Ruffo's company, CCS. The plan? Nelco would act as the middleman, leasing the computers to Philip Morris for use at those secret sites. The banks would wire the money directly to CCS to buy the equipment. After some time, Reiners would assure everyone the computers had been delivered and were up and running. But in reality? No computers ever showed up at any research site. None. Instead, Reiners and Ruffo funneled the money straight into their own pockets, buying real estate, stocks — anything they wanted. And all the while, the banks thought they were funding a legitimate, cutting-edge tobacco research project.

To keep the illusion airtight, Reiners insisted on iron-clad confidentiality agreements. The banks were told, "This project is so sensitive, you deal only with me. No calls, no questions, no direct contact with Philip Morris." Total secrecy was the rule of the game. Anything else, and the whole operation could come crashing down. The pair knew how to keep the game going: they made interest payments on time, keeping the banks off guard and their suspicions low.

But in 1996, everything started to fall apart. The scheme was unravelling quietly, and fast. It started with a sharp-eyed executive at the Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan. He became suspicious of the signature on one of the documents. Something about it didn't seem right. So he did what no one else had thought to do, he picked up the phone and called Philip Morris directly. That one call shattered the illusion. Philip Morris had never heard of Project Star, the signature on the document was fake, and they certainly weren't leasing hundreds of millions of dollars' worth of computers for secret overseas research labs.

The FBI was brought in immediately, and what they found was a fraud so detailed, so carefully crafted, it almost didn't seem real. They began quietly tracing the flow of funds: banks lending millions, computer contracts that didn't exist, equipment that was never delivered. And two men at the center of it all, John Ruffo and Ed Reiners.

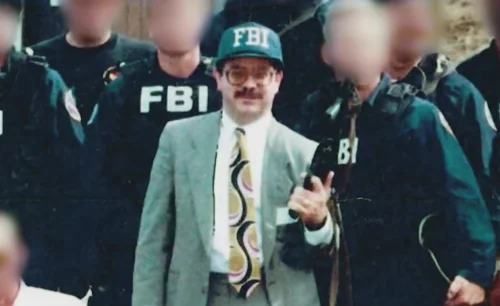

But instead of storming in with agents and handcuffs, the FBI decided to set a trap. So, they created a decoy office in Rye Brook, New York, just outside Philip Morris's actual Rye Brook campus. The building was a suburban metal and glass complex, tucked among manicured lawns and ponds. From the outside, no signage or markers gave away its purpose. Inside, however, it was a fully functional trap. Agents turned a conference room into a fake satellite office for Philip Morris Capital Corporation, complete with undercover officers pretending to be Philip Morris executives. The FBI had Signet and NationsBank ask for a meeting with Ed Reiners at the fake office — a live confirmation that Reiners actually represented Philip Morris. All to lure in Reiners and get him to reaffirm the con, on tape, in person.

On March 19th 1996, Reiners walked into that office, expecting just another meeting to grease the wheels of their fake project. What he didn't know was that the office was wired. The agents were listening. The moment he confirmed the existence of Project Star and acknowledged the financial arrangements, they had what they needed. FBI agents swarmed in and arrested him on the spot. Some of the most powerful pieces of evidence in the eventual trial would be the audio and video recordings made during that fateful FBI sting in Rye Brook, New York.

They had the hook. Now it was time to reel in Ruffo.

When news of Reiners' arrest reached John Ruffo, he didn't run. Not yet. He stayed calm, collected, as if he'd anticipated the possibility and already had a plan. By this point, Ruffo knew the walls were closing in. The FBI had seized bank records, intercepted communications, and found a trail of shell companies, fake invoices, and ghost accounts, all pointing directly to him. Behind the scenes, investigators were dissecting the fraud's machinery, and what they uncovered was more elaborate than anyone first realized. Far from a simple scam, Ruffo and Reiners had constructed an intricate web of deception, complete with fabricated offices, elaborate budgets, and convincing technical requirements. It all centered on that fictitious, top-secret research project for Philip Morris. This was no casual name drop, the real power of their con lay in the details. Investigators traced documents describing fully developed office locations — offices on Madison Avenue in New York, phony suites in New Jersey, and supposed technical hubs upstate. Each site came with its own set of blueprints, floor plans, and technical demands, presented as authentic requests from Philip Morris executives.

The budgets were equally exhaustive: multi-page breakdowns of hardware purchases — IBM computers, network servers, workstations, and even specialized air filtration systems for the labs. The numbers ran into the tens of millions, with precise schedules for delivery and installation.

Even more audacious was how Ruffo and Reiners manufactured credibility at every turn. To keep banks at bay, they mandated strict confidentiality agreements, forbidding anyone from contacting Philip Morris directly, claiming trade secrecy. This maneuver not only escalated the sense of urgency, but insulated the fraud from outside scrutiny, buying the conspirators precious time. When banks did push for verification, they were met by impersonators and forged documents. Some banks insisted on seeing an incumbency certificate, a document that verified Reiner's authority to represent Philip Morris, with an official seal, and signed by an executive at the company. Ruffo and Reiners created the certificates on genuine-looking Philip Morris letterheads with phoney seals. For the the signature they approached Diane McAdams, an executive at Philip Morris. They posed as a radio station telling her that she'd won a competition. To claim her prize, they said, she'd need to sign a release form and send it to them. She fell for the story, and unwittingly supplied them with a perfect specimen of her signature, which they recreated on the certificates. To back up the fake certificates, Ruffo and Reiners needed an accomplice to impersonate Diane McAdams over the phone. Ruffo persuaded one of his employees at CCS, a single mother from New Jersey named Judy Rose Bachiman, to play the role. Her conversations with bank investigators sealed the deal for several multi-million-dollar loans.

At times, Ruffo and Reiners choreographed entire site visits, complete with hastily rented office furniture and staged employees performing "research". Investigators later obtained testimony from participants who said they'd answered newspaper ads for temporary research assistants. These people were brought in, handed scripted lines, and told to dress professionally and move boxes, or type at computers.

The documentation trail was a masterpiece of forgery — a mosaic of fabricated contracts, purchase orders, and letters on what appeared to be genuine Philip Morris letterheads. They generated phony project timelines, and created accounting ledgers to support vast equipment lease transactions.

The fictional deals seemed so substantial, so well-organized, that investigators believe some banks assigned entire teams to manage their relationship with Ruffo's company. Millions were transferred based on these phantom equipment leases — computers that were never built, for projects that did not exist. Ruffo and Reiners had set up shell companies, like Worldwide Regional Exports, to layer transactions and cover their tracks. In some cases, funds borrowed from a new bank were used to pay interest on old loans, echoing the frantic shuffle of a Ponzi scheme.

By the time investigators connected all the dots, they realized how thoroughly the pair had exploited weaknesses in banking protocols, conjuring up an entire universe of fake research and facilities.

It wasn't long before John Ruffo was indicted on more than one hundred fifty counts, including bank fraud, wire fraud, money laundering, and conspiracy. His trial began in a packed federal courtroom in Lower Manhattan, and attracted intense media attention. Over several weeks, lawyers, bankers, and investigators crowded the chambers, as prosecutors meticulously unraveled the threads of one of America's largest bank frauds. The air was heavy with tension. Each day brought fresh revelations. Outside, TV crews clustered on the courthouse steps, while inside every seat was filled with reporters, and anxious employees from banks caught in the scheme. This was more than just a showdown over money. It was a rare, full-length glimpse into the machinery of deception that had fooled an entire financial system.

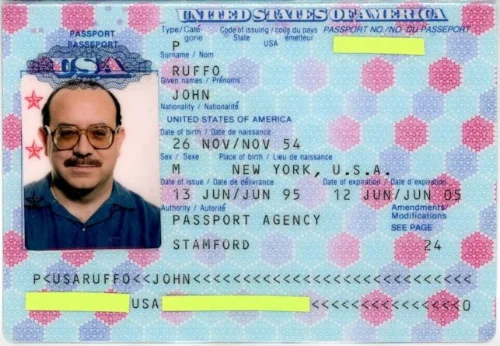

Ruffo's bail was set at an unprecedented $10 million. To secure his release, six members of his family — including his wife, his mother, and his mother-in-law — had to put their homes on the line as bond collateral.

In the heart of the trial, a telling detail emerged, one that captured just how far Ruffo and Reiners' deception had reached into the world of high finance. On the witness stand, a banker recalled an internal memo, hastily scribbled on a memo pad, where he'd documented his concerns over a key piece of paperwork: the incumbency certificate that supposedly empowered Edward Reiners to sign on behalf of Philip Morris. The signature, he noted, looked odd. The bank's legal counsel took these doubts seriously. In court it was revealed that he'd strongly advised obtaining a properly notarized version of the document. But urgency, and the assurances of secrecy, won out. Despite the advice, senior bank officers felt pressure to keep the deal moving. They overruled the recommendation, accepting the questionable documentation, and the mysterious aura of Project Star, at face value. That scribbled note would later stand as a symbol for the risks of ignoring gut instincts, and good legal guidance — one small moment in a web of decisions that allowed the fraud to unfold.

John Ruffo's defense couldn't counter the trove of evidence, including wire transfers and asset seizures. The trial ended with him being found guilty on all counts. The judge sentenced him to 17 years in federal prison, and ordered full asset forfeiture.

The fate of Ed Reiners was decided outside the glare of a full trial. He pled guilty to bank fraud and money laundering. At sentencing, the court acknowledged his extensive cooperation. He received a prison sentence of 16 years and 10 months. The judge ordered Reiners to pay $250,000 in restitution, and nearly all assets controlled by him and Ruffo — over $200 million — were ordered to be seized and liquidated, to reimburse the banks.

Despite the scale of the crime, John Ruffo was granted bail while awaiting sentencing. Why? Partly because prosecutors had already recovered a significant portion of the stolen money, and partly because Ruffo had no prior criminal record. He came across as cooperative, respectful, harmless. But most importantly because no one, not even seasoned law enforcement, believed he would actually run. He had a wife, a family, a life to return to after serving his sentence. And the money? Everyone assumed the government had frozen or tracked all of it.

But John Ruffo had a plan, and even as the courts moved toward sentencing, that plan was already in motion. After the verdict, John Ruffo didn't panic. He didn't try to cut a deal, or beg for leniency. Instead, he did something else. He waited. He stayed in his Manhattan home with Linda. He followed the rules, at least outwardly. He made his court appearances, attended pre-sentencing interviews, let the system believe he was cooperating. And maybe he was. But in the background, quietly, methodically, he was planning something else.

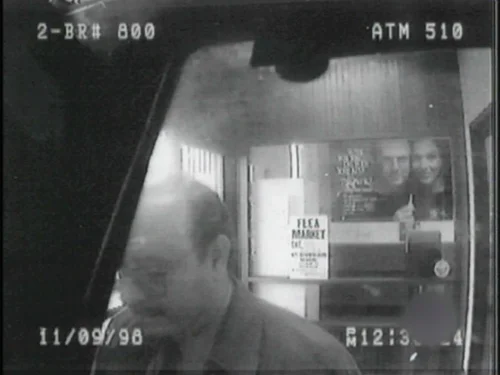

That morning, Ruffo told Linda he was heading out to turn himself in. He was due to report to Federal Correctional Institution Fairton, a medium-security prison in southern New Jersey, to begin serving his 17 year sentence. He packed a bag. He gave no sign of stress or hesitation. He kissed his wife goodbye, and walked out the door. Surveillance footage later showed him stopping at an ATM in Manhattan, where he withdrew $600 in cash, the maximum daily limit. He didn't use a disguise, didn't try to hide. Just stood there, calm and composed.

Then... Nothing.

By that evening, his green Ford Taurus was found abandoned in long-term parking at JFK Airport. But there was no sign Ruffo had boarded a flight. No passport activity, no luggage, no leads. He was gone.

The moment John Ruffo missed his prison surrender date, the manhunt began. At first, investigators thought maybe he'd panicked. Maybe he was hiding nearby, waiting to turn himself in, a few days late. They checked hospitals, hotels, local airports. But the moves were too clean, too deliberate. It wasn't a panic move, it was a plan.

The U.S. Marshals took the lead. Working with the FBI and Interpol, they began scouring airports, financial records, border crossings. Ruffo's photo was distributed nationwide. Warrants were issued. His accounts were frozen — at least, the ones they knew about.

But Ruffo had a head start. He'd studied the system. He knew how investigations worked. He knew what red flags to avoid, how to operate just below the radar. Investigators now believed he'd stashed millions in offshore accounts, far beyond what had been recovered in court. Enough to fund not just a few weeks on the run, but an entirely new life. He may have had a fake passport, a new identity, and travel documents ready long before sentencing.

Theories emerged quickly. Maybe he flew out under an alias. Maybe he crossed the border into Canada or Mexico and vanished by land. Maybe he never even left New York, just slipped into the underground and changed his face, his name, and everything else.

But one thing was clear early on: he was good at this. He didn't leave digital breadcrumbs. He didn't contact friends or family. No intercepted emails, no hidden burner phones, no sightings. The man who built a $350 million lie had now pulled off something even more impressive — he'd erased himself.

And then came the fallout. Just three months after his disappearance, the government made good on its warning. The homes of his wife, his mother, his mother-in-law, and others were seized as forfeiture for the $10 million bond he'd forfeited by fleeing. They lost everything. Not just their property, but the illusion that the man they loved had ever planned to come back.

But there was another side to John Ruffo that even his closest associates didn't fully understand. Behind the scenes of his legitimate computer business, Ruffo was living a double life that would make his eventual disappearance all the more mysterious. In the early 1990s, while Ruffo was running his computer company out of New York City, he'd developed a relationship with the FBI that went far beyond what anyone imagined. According to investigators, the Federal Bureau of Investigation had contracted Ruffo and his company for work during this period. But this wasn't your typical government IT contract. Part of Ruffo's business was being used as a "front company", with FBI agents actually placed inside the operation to give it legitimacy. The target? Soviet agents, during the final years of the Cold War. While Ruffo was presenting himself to the banking world as a simple computer equipment reseller, he was simultaneously helping the FBI track Soviet operatives. CCS wasn't just selling IBM computers, it was serving as a sophisticated intelligence operation.

But here's where it gets even more intriguing. When Ruffo disappeared in November 1998, the FBI initially didn't tell the U.S. Marshals — the agency responsible for hunting him down — about his role as an informant. Why would they withhold this crucial information? John Von Arnen, a former employee at CCS, believes he knows the answer.

"The day that he did not turn himself in, and he left the country, I believe to this day there's got to be somebody in the FBI that helped him escape," he says. Von Arnen isn't just speculating. He worked inside the company during the period when it was serving as an FBI front, he saw the operation from the inside. And his theory suggests something far more sinister than a simple case of bureaucratic oversight. If Von Arnen is right, it would mean that someone within the FBI — possibly someone in a position of significant authority — actively assisted one of America's most wanted fugitives in evading justice.

But Ruffo's intelligence connections may have gone even deeper than his FBI work. In diaries he left behind, Ruffo spun what investigators call "an exotic Cold War tale". He wrote about alleged connections to a Soviet computer engineer whose defection was sought by U.S. officials. Was this just another Ruffo fabrication? The man was, after all, what former Deputy U.S. Marshal Barry Boright described as "a pathological liar".

"He was a fraud guy. Half of everything in his life was a lie," he said of Ruffo. But here's what makes it complicated: some of Ruffo's stories checked out. ABC News actually tracked down a man who claimed to be the Russian national Ruffo had written about. This person corroborated some of Ruffo's stories, though he denied other claims.

But here's the troubling question: if half of everything in Ruffo's life was a lie, as Deputy Marshal Boright suggested, which half was true?

The timing of these intelligence connections is crucial to understanding Ruffo's escape. By 1998, when he disappeared, Ruffo possessed knowledge that could potentially embarrass the FBI, or compromise ongoing operations. He knew which agents had worked undercover in his company. He knew details about Soviet tracking operations. He had photographic evidence of high-level FBI relationships. In the intelligence world, people with that kind of sensitive knowledge don't just walk away clean, they're either protected or eliminated. When Ruffo fled, he made no mistakes. For a computer salesman from Brooklyn, this was a remarkably professional disappearance — almost as if he'd been trained for it. The U.S. Marshals have been hunting John Ruffo for over 25 years. They've followed leads and pursued tips from around the globe, but they've never found him. Maybe that's because they were never meant to. Perhaps we should be asking not just where John Ruffo went, but who helped him get there.

Fast forward to April 2001, nearly three years after Ruffo walked away from his prison surrender. In Duncan, Oklahoma, a town of about twenty thousand, a man claiming to be John Ruffo walked into several community banks, trying to open an account and receive what he said was $250 million in wire transfers from Nigeria. The town's Chief of Police Ronnie Ward, and local bankers, noted the man's East Coast accent stood out in the heartland, making him stick out like a sore thumb. When a teller finally matched him to a "wanted" poster, it became the first credible tip since Ruffo disappeared. But by the time U.S. Marshals moved in on his motel, he was gone again, vanished without a trace.

So how did he end up in Oklahoma? Ruffo might have been trying on a new identity — using his real name at first to test it out, or maybe he slipped up. He may have been scouting small-town banks to quietly set up accounts where he wouldn't be recognized. Maybe he was testing the waters for big transfers. If Ruffo had access to overseas funds, as investigators believe, he needed a place to receive it. Smaller banks in rural areas are often less scrutinized, making them an appealing starting point. Reappearing could have been intentional, a move to check how tight the net was. Or it might have been a mistake, a moment where confidence met complacency. If he really showed up using the name John Ruffo, that's either bravado, or a gamble.

It's still unconfirmed that the man in Duncan was definitely Ruffo, but it's the kind of lead investigators relish. It could have cracked the case wide open. Instead, it vanished, like Ruffo himself. Later that same year, his wife Linda filed for divorce. The life they'd once shared together was officially over.

For years, there was nothing. Then, in 2016, something strange happened. That August, a regular season game between the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Boston Red Sox suddenly became the center of a nationwide manhunt. Among the thousands packed into Dodger Stadium, one face caught the attention of both a viewer at home and, soon after, the U.S. Marshals. Carmine Pascal, John Ruffo's cousin from New Hampshire, was watching on TV when the broadcast cut to a close-up behind home plate. He saw a balding man with a mustache, wearing a blue t-shirt, seated just four rows up.Pascal was convinced, it was his cousin Johnny. He froze the screen and immediately called the U.S. Marshals. Carmine recalled the moment:

"I'm watching and right behind home plate, they did a close-up of the batter and there's Johnny. And I said, 'Holy Christ, there he is.' I froze the frame, kept it right in front of me."

The tip was rare, one accompanied by video evidence. Deputy Marshal Pat Valdenor, based in L.A., began investigating the fan's identity. "It does look like him, it could be him, so that was my starting point, that was the lead that I got," Valdenor recalled. Marshals contacted the Dodgers, tracing the exact seat: Section 1, Row EE, Seat 10. Directly behind home plate, where cameras often pan.

But the investigation soon hit a snag. The original ticket holder had given the ticket away, and as is typical with coveted seats, the ticket had passed through several hands before landing with the mystery man seen on television. For more than five years, investigators poured over footage, chased names, and checked records. But each ticket trace led further from the answer. Marshals released the fan's image to the public as the Dodgers made a run toward the National League Wild Card game, hoping a tip might resolve the mystery.

In October 2021, their persistence finally paid off. A tipster, after seeing the image circulate in news reports, came forward and provided credible information. Marshals conducted a swift background check and traveled to a Los Angeles suburb to fingerprint the man behind home plate. The results were clear. He was not John Ruffo, there was no match. The Dodgers fan was simply a regular attendee who happened to resemble one of America's most wanted fugitives.

For Ruffo's cousin, Pascal, it was a moment of dashed hope. For the U.S. Marshals, it was the closure of one of the most frustrating leads in a decades-long pursuit. Yet the investigation was remarkable for its thoroughness, with the Marshals leveraging advanced facial recognition from TV broadcasts, and trawling through ticketing records.

The sighting was a dead end, but it reignited interest in the case. In 2021 the U.S. Marshals launched a new nationwide billboard campaign. They posted his face across the country. They offered a $25,000 reward. They re-interviewed family, friends, former associates. His wife Linda still claimed she had no idea where he went. Some investigators believe she really doesn't know, others aren't so sure.

John Ruffo's story isn't just one of financial fraud, it's also a window into a complex, troubled mind. Behind the schemes and the dazzling lies, there's a man with a deeply troubled psychological profile that helps explain how he manipulated everyone around him, and vanished. Former Deputy U.S. Marshal Barry Boright described him bluntly as "a pathological liar", but that's just scratching the surface. He believes that Ruffo has the classic traits of someone with an antisocial personality: superficial charm, lack of remorse, deceitfulness, and a readiness to exploit others. Ruffo wove grand narratives about his life — tales of secret CIA work, capture by the Vietcong during the Vietnam War, and Soviet intelligence collaborations. All of these were designed to impress, confuse, and control. This grandiosity masked a man who thrived on deception. Even those close to him describe a man who was endlessly fascinating, but impossible to truly know. His charm disarmed suspicion, while his lies insulated him from consequences. He wasn't simply running a fraud. He was living a constructed identity, a performance as intricate as the financial schemes he engineered.

John Ruffo pulled off one of the most audacious frauds in American history, then vanished like a ghost. But how does someone disappear in the modern age, with every agency and law enforcement group hunting for them? Over the years, experts and investigators have pieced together several plausible theories about how Ruffo might have stayed off the grid for decades. It's widely believed Ruffo had access to multiple fake passports and identification documents. As someone who knew the system inside out, he'd have known that securing credible forged IDs would be critical. These would allow him to cross borders, open bank accounts, and live under assumed names without drawing suspicion. Ruffo is known to have used multiple aliases, including John Russo, Jack Nitz, Bruce Gregory, John Peters, and Charles Sanders.

Authorities recovered some of the stolen funds, but Ruffo reportedly had access to millions more hidden in offshore accounts in the Caribbean, South America or Europe. These accounts could provide a steady flow of cash to fund his lifestyle and any false identities. Unlike some fugitives who flaunt their money, Ruffo was used to keeping a low profile — no yachts, no flashy parties, no obvious signs of wealth. He could have lived quietly in small towns or abroad, blending in with locals and avoiding attention. He may have built a new social network, people unaware of his past, or willing to protect him in exchange for favors or financial support. Living off the grid isn't just about hiding, it's about having the right connections.

And remember, Ruffo was a master strategist. This wasn't a last-minute escape. Investigators believe he planned his disappearance for years, anticipating every move law enforcement might make. Successfully disappearing and leaving no digital footprint requires meticulous forethought.

But, what of Ed Reiners? He'd been a respected business executive before he became the crucial partner and co-conspirator in a massive fraud. Reiners had spent two decades working in Philip Morris' Information Systems division, before being laid off in 1992. It was shortly after that when he approached Ruffo with an idea that would evolve into Project Star. Unlike Ruffo, whose charisma and deception drove the scheme, Reiners brought insider knowledge and corporate credibility that helped make the scam believable. Reiners served roughly nine years of a 16-year and 10-month sentence, finally being released in 2005. After prison he mostly disappeared from the public eye, living quietly away from the spotlight. In the few interviews he's given, he's reflected on the audacity of the scheme, and its fallout.

His story is a stark contrast to Ruffo's — one man who faced the consequences, the other who vanished.

As for the banks? Many wrote off the losses as the cost of doing business, though not without tightening their protocols. This case led to more stringent lending standards, especially when it came to large, private, or confidential commercial loans. Some institutions faced government scrutiny over how they were so easily manipulated. But Ruffo and Reiners didn't just trick institutions, they tricked people, real people — relationship managers, risk officers, loan specialists — all of whom signed off on the transactions based on what they believed was legitimate, well documented business. Some of them had worked for decades without incident. They followed protocol But when the fraud collapsed, scrutiny turned inward. Following the arrests, banks launched aggressive internal reviews. Staff involved in the deals were interrogated, personnel files were re-opened. Some employees were reassigned, others were terminated. And several saw their careers stall permanently. They weren't charged with crimes, but the implication was there: "How could you let this happen?" And in high finance, reputation is everything. At least one mid-level executive, according to reporting at the time, was forced into early retirement. Others reportedly left the industry.

For the institutions left in its wake, the case wasn't just embarrassing, it was a wake-up call. In the years after Ruffo vanished, banking regulations tightened. Lenders began re-evaluating how they vet clients, especially when it comes to massive, confidential, or unusual corporate loans. Internal due diligence protocols were rewritten, executive-level sign-offs became stricter, and for any deal involving secrecy the scrutiny increased considerably. The phrase "Project Star" became a kind of whispered cautionary tale inside financial institutions. It stood for what happens when credibility is mistaken for proof.

Law enforcement agencies, too, took notice. The U.S. Marshals Service and the FBI have both made changes in how they monitor white-collar defendants awaiting sentencing. Ruffo had been granted the freedom to report to prison voluntarily, something not uncommon for non-violent offenders at the time. But in the years that followed, judges became more cautious about such arrangements. Bail decisions in high-value fraud cases began to consider not just the flight risk, but the psychological profile and financial reach of the defendant.

And one more thing changed: public perception. Before Ruffo, white-collar crime rarely captured national attention. It was seen as boring — paperwork, numbers, and gray suits. But this case — with its massive scale, its vanishing act, and its trail of broken trust — changed that. It proved that white-collar crime could be just as bold, just as devastating, and just as cinematic as anything on the FBI's "Most Wanted" list.

In the end, John Ruffo's mind was his greatest weapon. A blend of intelligence, charm, and cold calculation made him almost impossible to catch. It's a chilling reminder that the biggest criminals aren't always the loudest. Sometimes they're the quiet ones, who disappear into the crowd.

More Episodes

The Man in Room 1046

In 1935, a man with no luggage, using a fake name, was found tortured inside a locked room at the Hotel President in Kansas City. His last words were a lie, and the police had no weapon, no suspects, and no motive Read more

The Green Bicycle Case

In the summer of 1919, a young woman was found dead on a quiet country lane in Leicestershire, a bullet wound in her head. The only clue? A mysterious man seen with her shortly before her death, riding a distinctive green bicycle. Read more