The Killing of Maximum John

In May 1979, the American justice system was shaken to its core. Federal Judge John H. Wood Jr. — known by criminals as "Maximum John" for the harsh sentences he handed down — was shot and killed by a sniper outside his San Antonio home.

We explore the powerful drug trafficking empire of Jamiel "Jimmy" Chagra, the man who ordered the hit, and the notorious contract killer he hired to carry it out, Charles Harrelson, the father of actor Woody Harrelson.

San Antonio, Texas. May 29th, 1979.

The morning sun casts long shadows across the manicured lawns of the Chateau Dijon. It's a name that aspires to French elegance, but the architecture is pure 1970s American suburbia: sturdy brick townhomes, neatly trimmed hedges, covered carports. It's a place of quiet success, a community of doctors, oil executives, and prominent lawyers. The kind of place where nothing truly bad is ever supposed to happen. The air is warm, thick with the promise of a hot Texas day. The only sounds are the cooing of mourning doves and the distant drone of early traffic on the Loop 410 freeway.

Inside one of the townhomes, a 63-year-old man is following the precise rituals that have governed his life for decades. His name is John Howland Wood, Jr. He is a man of rigid habits and unshakeable convictions. Just after 8:30 AM, he walks out of his front door. He's dressed impeccably in a dark conservative suit, a crisp white shirt, and a perfectly knotted tie. He carries a leather briefcase. His wife, who he always kissed goodbye, watches from the door. It's a scene of domestic tranquility that has played out thousands of times.

He walks along the paved path toward his car, his footsteps echoing faintly in the morning stillness. He gets into his grey Buick sedan — a sensible car for a sensible man. He is due in court. He has a docket to manage, sentences to hand down. He will never make it.

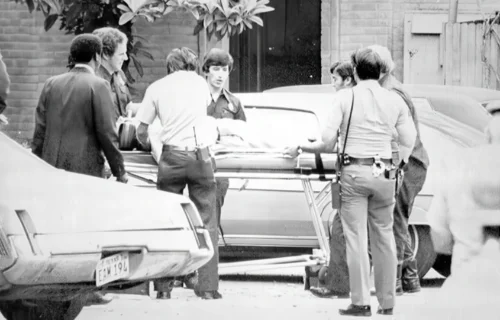

From a vantage point across the driveway, hidden in a thicket of overgrown brush, another man is watching. He's not a resident, he doesn't belong here. He is a predator who has stalked his prey with chilling patience. He raises a high-powered hunting rifle to his shoulder, the cold metal a stark contrast to the warm air. He squints, looking through the telescopic sight. He sees Judge Wood get out of the sedan again — the engine wouldn't start. The world narrows to the man in the crosshairs who is leaning across the front seat to retrieve his suitcase. A single shot, it's all it takes. The bullet, a .240 Weatherby Magnum, finds the judge's back, and tears through his body.

For a few heartbeats, there is only silence. The birds have stopped singing. But the quiet of the morning is shattered. Not just for that suburban street in Alamo Heights, but for the entire country. Because Judge John H. Wood Jr was not just any judge. He was a United States federal judge, appointed for life — a symbol of the bedrock of American law. And this was not just a murder, it was an assassination — the first assassination of a federal judge in the 20th century. It was a message, sent with a single, devastatingly accurate bullet: no one is untouchable. It was an act of war against the judicial system itself, and it would trigger one of the largest, most complex, and most fascinating manhunts in the history of the FBI.

This is a story about a judge who believed in order in a world of chaos. It's a story about a charismatic, cocaine-fueled drug lord who saw the law as just another obstacle to be removed. And it's a story about a cold-blooded, professional killer — a "gentleman hitman" — whose own son, improbably, would one day become one of the most famous and beloved actors in the world. This is the story of the hunt for the killer of Maximum John.

To understand why a man would risk everything to kill a federal judge, you first have to understand the judge, and the world he occupied. John Howland Wood Jr was Texas aristocracy. Born in 1916, his family tree was populated with lawyers stretching back generations. He was a product of the University of Texas law school, a man steeped in tradition, protocol, and a rigid sense of right and wrong. When President Nixon appointed him to the federal bench for the Western District of Texas in 1970, he saw it not as a job, but as a duty. His district was vast, stretching from San Antonio down to the Rio Grande Valley. And in the 1970s, that territory was Ground Zero for America's burgeoning drug war. It was a battleground. The post-Vietnam, post-Watergate era saw an explosion in the drug trade, with San Antonio serving as a primary distribution hub for Mexican marijuana and, increasingly, South American cocaine. Judge Wood looked upon this tide of narcotics not just as a crime, but as a moral stain, a force of chaos corrupting the nation, and he decided his courtroom would be the fortress that held the line.

He quickly earned a reputation, and a nickname that was whispered with fear in every cantina and backroom from Laredo to El Paso: "Maximum John." It wasn't just a catchy name, it was a statement of policy. The federal sentencing guidelines gave judges considerable discretion. Judge Wood chose to use none of it. For major drug traffickers, he had one setting: maximum. Life sentences were his specialty. He once sentenced a heroin dealer to 35 years — for contempt of court. He rarely granted pre-trial bail in narcotics cases, correctly assuming that multi-millionaire traffickers had the means and motivation to flee.

To the federal prosecutors he was a godsend, their greatest weapon. To the defense bar and their clients he was a tyrant in a black robe, the end of the line. A hearing before Maximum John wasn't a legal proceeding, it was a funeral.

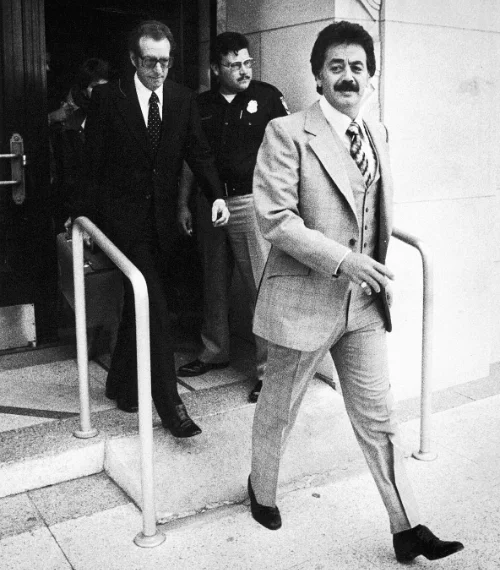

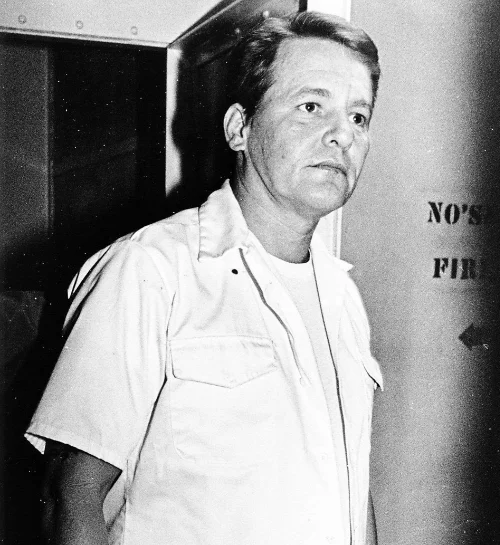

And in the spring of 1979, the biggest drug trafficker in the Southwest, a man who represented everything Judge Wood despised, was on a collision course with his courtroom. His name was Jamiel, or Jimmy, Chagra. If Judge Wood was the embodiment of the old-world Texas establishment, Jimmy Chagra was the king of the new-world criminal frontier. He wasn't some brutish thug. He was a third-generation Lebanese-American from El Paso, a man of immense charm, intelligence, and ambition. The Chagra family had started, like many immigrant families, in legitimate business: a produce company, and a rug store. But Jimmy, and his older brother Lee, saw a faster path to the American dream. They started smuggling marijuana from Mexico, and they were brilliant at it. By the late 1970s, Jimmy had built a logistical empire. He had fleets of airplanes, sophisticated communication systems, and a network of distributors that spanned the country. He graduated from bulky marijuana to high-profit cocaine, and his fortune exploded into the tens of millions. And he lived like it. Jimmy Chagra was a legend in Las Vegas. In an era of flamboyant high-rollers, he was the main attraction. He would stride into Caesars Palace, his entourage in tow, and drop hundreds of thousands of dollars at the craps table without flinching. The casinos loved him. They gave him the best suites, flew him in on private jets, and comped his every whim. He bought his wife, a striking Vegas showgirl named Elizabeth, everything she could ever desire. He was a folk hero in his hometown of El Paso, known for his generosity and charm. He was the CEO of a vast, illegal conglomerate, and he was living a life of unimaginable luxury.

But the bigger the empire, the more attention it draws. A massive federal drug investigation, codenamed "Operation Tri-State," had been meticulously building a case against the Chagra organization for years. In February 1979, the hammer finally fell. Jimmy was indicted on federal charges of masterminding a continuing criminal enterprise, the so-called kingpin statute. It was a charge designed specifically for men like him. And the judge assigned to preside over his trial in Austin that coming summer was John H. Wood Jr. Jimmy Chagra, the man who gambled for a living, immediately understood the odds. He wasn't just facing prison, he was facing Maximum John. For a man like Chagra — a man whose entire identity was built on freedom, wealth, and adrenaline — a life sentence in a federal penitentiary was a fate worse than death. The party would be over. Forever.

He panicked. His first move was through the system. His high-priced lawyers filed motion after motion demanding Judge Wood recuse himself. The argument was that Wood's "Maximum John" reputation proved he was incapable of being impartial. They claimed he had a personal vendetta against drug defendants. Judge Wood, a man who prided himself on his integrity, was insulted. He denied every motion, writing that a judge shouldn't be disqualified for being tough on crime. He would not be moved.

With his legal options exhausted, Chagra's desperation curdled into something darker. He turned to his younger brother, Joe Chagra. Joe was a criminal defense attorney in El Paso. He was smart, but he lacked Jimmy's swagger and nerve. He was part of the family business, but more as a consultant than an executive. He was the one Jimmy turned to when he needed a problem solved. In a series of frantic, hushed conversations, Jimmy laid out his terrifying calculus: Wood was going to convict him, Wood was going to give him life, and Wood would never, ever grant him bail. The trial was a formality. As Joe would later testify in a hushed courtroom, Jimmy looked at him and laid the proposition bare — the only way to stop the trial, the only way to avoid a life behind bars, was to kill the judge. For a moment, the sheer audacity of it hung in the air. This wasn't killing a rival or an informant, this was murdering a federal judge. It was an attack on the government itself.

But Jimmy Chagra, the ultimate gambler, had decided to go "all in". He told Joe to find him a hitman. Joe Chagra, the lawyer — the legitimate brother — was now tasked with procuring an assassin. He put out feelers through his network of shady clients and underworld contacts. He needed someone reliable, professional, and discreet. The name that came back was a legend in the Texas criminal underworld: Charles Harrelson.

Charles Voyde Harrelson was a killer, but he was no thug. He was a former Navy man, possessed of a disarming charm. He saw himself as a freelance problem-solver. He was a card shark, a womanizer, and a stone-cold professional. He'd been tried for the murder-for-hire of a businessman named Alan Berg, and found Not Guilty. But he remained incarcerated, awaiting trial for another contract killing, this time of Sam Degelia Jr, a Texas grain dealer. That trial ended in a hung jury, but prosecutors — convinced of his guilt — tried him a second time. This time, the verdict was Guilty. In August of 1976, Harrelson was granted parole, but he didn't taste a moment of true freedom. As he walked out of the Texas state prison, U.S. Marshals were waiting. They immediately took him into custody and transferred him to the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas, to complete an older sentence for a prior firearms charge. Finally, in 1978, he was released again. A free man, he returned to Texas — his reputation as a formidable contract killer not just intact, but enhanced by his ability to navigate and survive the justice system. He was back on the market, looking for a lucrative contract, just as Jimmy Chagra was growing desperate.

Joe Chagra arranged a meeting. The price was negotiated with the cool detachment of a business deal: A quarter of a million dollars, to alter the course of American legal history. The deal was struck. Harrelson went to work with the meticulousness of a craftsman. He persuaded his wife, Joanne, to visit a sporting goods store in dallas. There, using the possibly ironic alias "Faye King", she purchased a Weatherby .240 caliber rifle. It was a hunter's weapon, known for its incredible accuracy over long distances. In mid-May of 1979, he drove to San Antonio and checked into a motel. Then, he began to stalk Judge Wood. He was a ghost in the affluent suburbs. He learned the judge's routine — a creature of habit. He knew Wood lived at the Chateau Dijon, he knew which car he drove, he knew the precise time he left for the courthouse each morning. He meticulously scouted the area, walking the grounds, looking for the perfect sniper's nest. He found it in a patch of unkempt brush and mesquite trees across a small field from the judge's parking spot. It offered a clear, unobstructed line of sight of about 150 yards and, crucially, an easy escape route to the nearby freeway.

On the night of May 28th, Memorial Day, all the pieces were in place. Jimmy Chagra was very publicly losing money at the craps tables at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, building an ironclad alibi. Joe Chagra was in El Paso, nervously waiting by the phone. And Charles Harrelson was in San Antonio, the rifle by his side, waiting for the sun to rise.

The next morning, he was in position before the first residents had picked up their newspapers. He watched as Judge Wood emerged, said goodbye to his wife, and began his final walk. Harrelson raised the rifle, the stock fitting snugly against his shoulder. He looked through the scope. He watched the judge walk towards his car. He waited for a clear shot. He controlled his breathing. He gently squeezed the trigger. Harrelson didn't linger, he knew his shot was accurate. He lowered the rifle, slipped back through the brush to his car, and was gone, merging into the morning traffic, just another anonymous vehicle on the Texas highway. He'd earned his fee — he'd done the unthinkable.

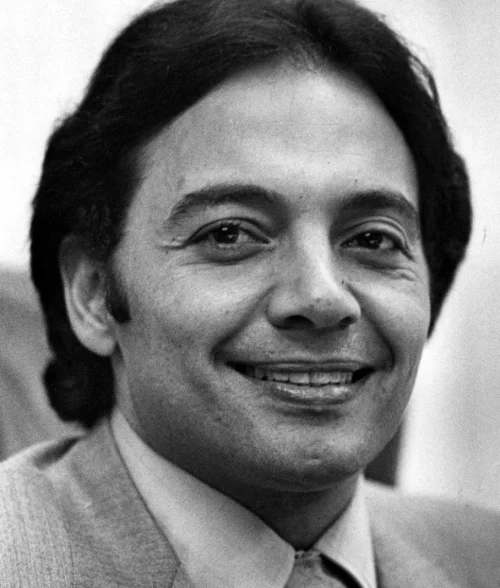

Back at the Chateau Dijon, the bubble of suburban peace had burst, replaced by the shriek of sirens. The first police on the scene found the judge with a single, fatal wound. The call went out almost immediately. This wasn't a local homicide, this was a federal case. Within hours, the FBI descended on San Antonio in force. The investigation was given a priority level reserved for acts of terrorism and espionage. It was codenamed "JUDKILL". Agents swarmed the apartment complex, interviewing every shaken resident, searching for any scrap of evidence. They found precious little. A single, gleaming brass shell casing from a .240 Weatherby rifle cartridge confirmed the killer had used a powerful and accurate weapon. They had a few contradictory witness descriptions of a small, tan car speeding away. But the murder weapon itself, the rifle, had vanished. It was a crucial piece of evidence, seemingly swallowed by the vast Texas landscape without a trace.

The pressure from FBI headquarters in Washington was immense. Director William H. Webster vowed that no resource would be spared. President Jimmy Carter described his assassination as "an assault on our very system of justice." The message was clear: find the killer, no matter the cost. The largest FBI investigation since the assassination of President John F Kennedy was officially underway. They had a dead judge, a shell casing, and a nation demanding answers. The question was, where on earth do you begin when the killer could be anyone, anywhere? The answer, as it turned out, was in a smoke-filled, high-limit casino room, hundreds of miles away in the glittering mirage of the Nevada desert.

In the initial days of the JUDKILL investigation, the FBI was drowning in a flood of information, and misinformation. The assassination of a federal judge was a national trauma, and the tip lines rang off the hook. Was it the work of the Mafia? A lone extremist? Agents chased down hundreds of leads, each one a potential path to the truth that ultimately dissolved into a dead end. They meticulously cataloged every threat ever made against Judge Wood, interviewing dozens of disgruntled inmates he had sent to prison. The investigation was a sprawling, frustrating search for a needle in a haystack the size of Texas.

But amidst the noise, one signal came through — faint at first, then stronger. Informants in the criminal underworld, and even some law enforcement sources, kept whispering the same name: Jimmy Chagra. The motive was so obvious it was almost blinding. Of all the criminals in the United States, none had more to gain from Judge Wood's sudden death. Chagra had the means, the money, and the absolute desperation — his trial was just weeks away. The assassination wasn't revenge, it was a preemptive strike. While Chagra's alibi — being seen by hundreds of people gambling in Las Vegas — was solid, the FBI knew that men like him operated through layers of insulation. They don't pull the trigger, they sign the check.

Jimmy Chagra became "suspect number one". The FBI began to apply a campaign of relentless, suffocating pressure. A team of agents was assigned to Chagra full-time. They followed him in unmarked cars, they sat at nearby tables in restaurants, they documented his every meeting, they wiretapped his phones. They leaned hard on his known associates, letting them know that the full weight of the federal government was coming down on the Chagra empire. Chagra, ever the gambler, tried to bluff. He brazenly called the JUDKILL task force in San Antonio himself, offering his "sincere condolences" and complaining that he was being unfairly harassed.

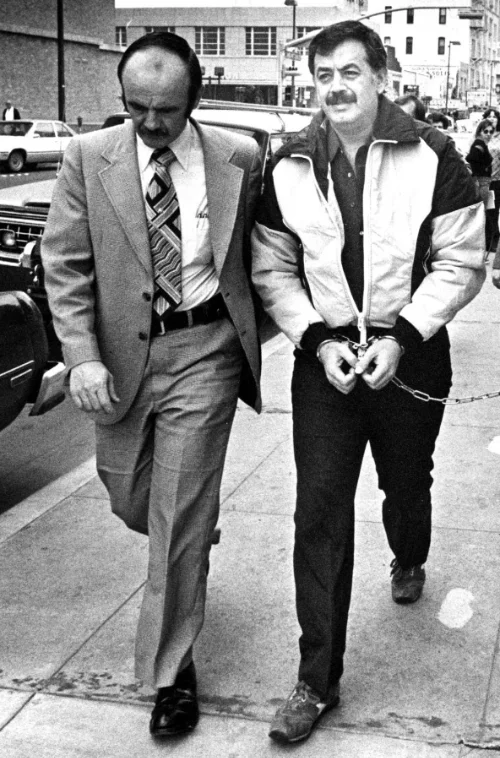

But the pressure was working. He became paranoid and erratic. He eventually went on the run, and was captured months later on his original drug indictment. But the FBI still lacked the crucial piece of evidence to tie him directly to the murder plot. They knew he was the architect, but they couldn't prove it. To do that, they needed to find the cracks in his organization. They knew that large conspiracies are like chains: they are only as strong as their weakest links. The first and most obvious weak link was the lawyer, Joe Chagra. The FBI zeroed in on him. Unlike his brother, Joe was not a hardened, lifelong criminal. He was a man of the law, tormented by his role in breaking it so profoundly. Investigators brought him in for questioning again and again. They played "good cop, bad cop". They laid out the evidence they had, subtly exaggerating its strength. They described in vivid detail the future that awaited him: conspiracy to commit murder, decades in a federal prison, the loss of his law license, the destruction of his family. The psychological weight became unbearable. Joe Chagra began to break.

The second, and perhaps most critical, link was Jimmy's glamorous wife Elizabeth, known to everyone as Liz. Liz Chagra was more than just a showgirl who married well. She was tough, smart, and fiercely — blindly — loyal to her husband. After the assassination, Jimmy needed to pay Harrelson the quarter-million-dollar fee. But with the FBI watching his every financial transaction, he couldn't move the money himself. So he entrusted the job to Liz. He gave her a suitcase filled with $250,000 in cash. She flew from Las Vegas to Florida, where she met a relative of Charles Harrelson. In a clandestine handoff, she delivered the payment. It was an act of absolute devotion, but it was also a catastrophic blunder. It created a tangible link — a money trail that forensics accountants could follow, connecting the Chagra family's wealth directly to the hitman.

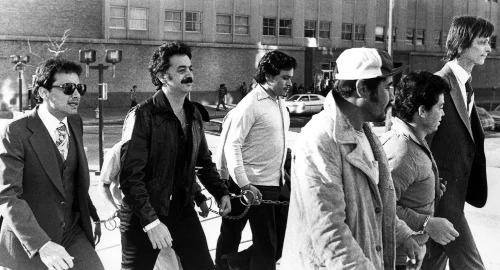

The FBI now had leverage on Joe and a money trail pointing towards the killer. And through Joe Chagra's increasingly detailed cooperation, they finally had the killer's name confirmed: Charles Harrelson. Finding a professional ghost like Harrelson was a challenge in itself. He moved constantly, using aliases, never staying in one place for long. But the FBI's net was tightening. They tracked his movements, intercepted communications, and finally, in September of 1980 — more than a year after the assassination — Texas Rangers located him.

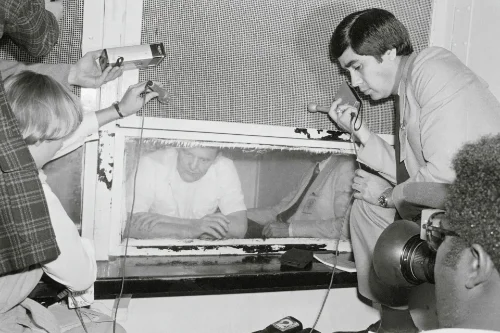

His arrest was not a quiet affair. It was a scene of pure, cocaine-fueled Texan madness. The officers spotted him on a highway and pulled him over. Seeing them, Harrelson panicked. He put a pistol to his own head, threatening to kill himself. What followed was a bizarre, six-hour standoff, all of it captured on police audiotape. High on a cocktail of drugs and paranoia, Harrelson began to ramble. He was, in his own mind, a key player in the secret history of the world. And then, in a moment of grandiose delusion, he made the confession that would seal his fate. He not only admitted to killing Judge Wood, he took credit for an even bigger crime.

Harrelson, his voice agitated and slurring slightly, told the police "You want to know who killed the judge? You're looking at him. But that's not all. I was in Dallas. I was involved when they got Kennedy."

The claim that he assassinated President John F Kennedy, was almost certainly a fabrication, a desperate bluff, or a drug-induced fantasy. But the detailed confession to the Wood murder was real, specific, and corroborated by details only the killer could know. He had just handed the FBI a confession on a silver platter. When he finally, peacefully, surrendered, the FBI had their trigger man.

As the investigation wore on, the FBI knew that finding the murder weapon was paramount. It was the one piece of physical evidence that could directly tie the trigger man to the crime scene. For nearly two years the rifle remained elusive. Then, in early 1981, they got the break they had been waiting for. During a search of Joe Chagra's home in El Paso, investigators found a hand-drawn map. It was crude, but its purpose was clear. It was a map leading to the spot where the components of the murder weapon had been discarded. The map lead the authorities to a lake outside Dallas. A massive operation was launched. Scores of federal agents and highly-trained Navy frogmen descended on the area, meticulously searching the murky water. They grid-searched the lake bed, their expensive equipment probing the mud and silt. But after days of fruitless, costly effort, the search was called off. They found nothing. The map, it seemed, had led them on a wild goose chase.

And then, just five days later, a break arrived in the most unexpected form. It didn't come from a federal agent, or a high-tech search. It came from a 25 year-old man named Thomas Hickson who earned his living foraging for aluminum cans along the back roads of Texas. As Hickson made his usual rounds near that very same lake, searching the ditches for discarded cans, his eyes fell upon something out of place. It was not a can, but a piece of dark, polished wood. He picked it up. It was a rifle stock. Unaware of its immense significance, he held in his hand the very thing the massive federal operation had just failed to find. He turned it over to the authorities. Federal investigators quickly confirmed their belief: it was the stock from the Weatherby rifle used to kill Judge John H. Wood Jr. The evidence that had eluded scores of agents and divers had been found by accident, by a man picking up cans.

With the trigger man in custody, his confession on tape, and now with a key component of the murder weapon itself recovered, the entire conspiracy was now laid bare. It was a pyramid of guilt. At the top was the mastermind, Jimmy Chagra, who ordered the hit out of a desperate desire to save his own skin. Below him was the facilitator, his brother Joe Chagra, who made the arrangements and was now the government's star witness. The crucial link was the courier, Liz Chagra, who had unwittingly created a money trail. And at the base — the instrument of their design — was the killer, Charles Harrelson, now in custody with his own bizarre confession on tape.

Between 1981 and 1982, the federal grand jury handed down the indictments. Charles Harrelson was charged with murder and conspiracy. Jimmy Chagra was charged with masterminding the plot. Liz and Joe Chagra were charged as co-conspirators. For the Department of Justice, it was the culmination of years of painstaking work. It seemed like an open-and-shut case, a textbook example of how the system, when attacked, could defend itself.

But they had underestimated the resources and the audacity of their main target. Jimmy Chagra, still possessed of a vast fortune, began to assemble a legal dream team. And to lead it, he hired the one lawyer in America who was most feared by the federal government — a brash, brilliant, and utterly fearless defense attorney from Las Vegas, a man who had built a career defending mobsters, and taking on unwinnable cases. His name was Oscar Goodman.

The FBI's chase was over. The prosecutors, led by the tenacious Assistant U.S. Attorney James Kerr, were confident. But the real war, the one that would be fought with words, strategies, and theatrical flair in a court of law, was just about to begin. And it would deliver a shock to the system almost as profound as the assassination itself.

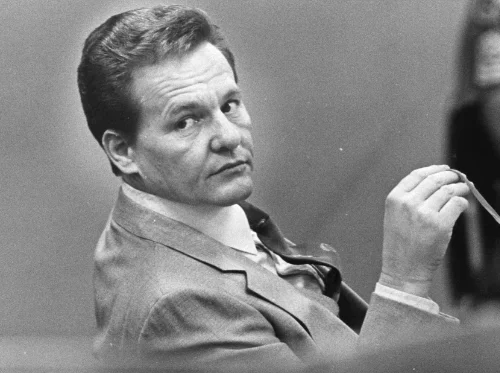

The first trial, in the autumn of 1982, was that of Charles Harrelson, his wife Joanne, and Liz Chagra. Jimmy Chagra was tried separately because Joe wouldn't testify against his brother, but had agreed to testify against the others. The three accused sat in a federal courtroom in San Antonio, the very city where the murder had taken place. Charles Harrelson was not the wild-eyed, paranoid man from the roadside standoff. He was a different creature entirely. For the most part he appeared utterly relaxed, a man at ease in the high-stakes theatre of the courtroom. He would chat amiably with his attorney during breaks, he'd mug for the newspaper sketch artists, and when a witness would testify about his legendary skill with a rifle or a deck of cards, a broad, genuine smile would spread across his face. He seemed to be enjoying the attention, the infamy.

But while he may have seemed calm, the prosecution was building a cage of evidence, piece by damning piece. Their case didn't begin with the dramatic confessions. It began with the mundane, tangible evidence. It began with a car, and a gun. The prosecutors called a former friend of Harrelson's, a man named Gregory Goodrum, to the stand. Goodrum testified that in June of 1979, just after the assassination, Harrelson had asked him to do a favour: deliver an Oldsmobile Cutlass to Houston. When Goodrum asked why, Harrelson's reply was chillingly casual: he said he had "used it on a job." The prosecution alleged this was the getaway car. Goodrum then recalled an earlier visit to a ranch with Harrelson. The defendant, he said, had proudly shown him a sleek Weatherby rifle, complete with a scope, and remarked that Weatherbys were his favourite guns. The link was made: the same type of rifle used to kill the judge was Harrelson's weapon of choice.

With the physical connections established, the prosecution moved to paint a portrait of the defendant's mind. They wanted the jury to understand that this was not a man who killed in a fit of passion, but a professional to whom life was cheap. They called another friend to the stand, a man named Pete Kay, himself once acquitted of two murders. Kay testified that Harrelson, after serving time for a previous killing, had once described a human head as being "just a watermelon with hair on it." The courtroom was silent. Under Harrelson's flat, unblinking stare, the witness suddenly seemed to lose his nerve. Pete Kay fidgeted on the stand, backtracking, conceding that perhaps it wasn't Harrelson who had said it, perhaps it was he who had made the gruesome comment. But the image had been planted in the jury's mind.

The prosecution's next witness, a wealthy rancher and former heroin addict named Hampton C. Robinson III, had no such reservations. He testified that Harrelson had boasted to him that "killing people and getting away with it is my long suit." He told the jury Harrelson had a detached, philosophical view of the Wood assassination, claiming the judge "didn't get killed, he committed suicide by the way he sentenced people." Robinson also bolstered Harrelson's reputation as a marksman, recounting how he once watched Harrelson kill a turkey with a single shot from 200 yards away.

But the most devastating evidence was yet to come, drawn from Harrelson's own words. First, an FBI agent took the stand to read from what was described as a sort of memoir, written into an appointments calendar Harrelson had left with Hampton Robinson. The agent read an entry dated August 30th, 1981, written like a last will and testament:

"I'm sorry, not for me but for the pain I've caused others, both those who loved me and those who loved the people I've killed. But I've never killed a person who was undeserving of it."

The agent continued reading. The entry concluded with a final, macabre instruction.

"I wish to be cremated with absolutely no religious services. My ashes should be spread on the John H. Wood Jr Courthouse in San Antonio."

The courthouse had, of course, been named for the judge after his death. It was a confession wrapped in a final, defiant insult.

Then came the prosecution's star witness: Joe Chagra. Harrelson's lawyers fought strenuously to block his testimony. They argued that Joe had acted as Harrelson's attorney after the murder, and therefore their conversations were protected by attorney-client privilege. The objection was a crucial test. After hearing arguments, the judge ruled the discussions between the two men were not for legitimate legal advice, but were meant to further a conspiracy to cover up the murder. The privilege did not apply. Joe Chagra was allowed to testify. He took the stand, a nervous figure at the centre of a legal firestorm. The prosecutor asked him about a conversation he had with Harrelson. Joe Chagra looked across the courtroom at the man he had hired and delivered the final blow. "I asked him if he was the one who murdered Judge Wood," Joe said, his voice quiet but firm, "and he said he was."

Finally, in a risky move, the defense called Charles Harrelson himself to the stand. He needed to provide an alibi for the morning of May 29th, 1979. He testified that he was nowhere near San Antonio. He was in Dallas, he claimed, a busy man running a series of errands. But his description of those errands may have done him more harm than good. He testified that he was trying to collect bad gambling debts, he was buying a cashier's check to pay for a car he'd bought under a false name, and — in a moment of almost surreal detail — he said he was returning a golf putter he had borrowed from a friend. The purpose of borrowing it, he explained to the jury, was to determine how much cocaine he could stuff into its hollow shaft for a drug-smuggling scheme he was devising. It was an alibi built entirely on a foundation of other crimes. He was, in his own telling, a con man, a gambler, and a drug trafficker. The jury was left to decide if he was also a murderer. They didn't take long to make up their minds. The weight of the evidence — the car, the rifle, the testimony of his friends, his own diary, and his own confession to Joe Chagra — was simply overwhelming.

The jury deliberated for 18 hours at the end of an 11 week trial. They found Charles Harrelson, and his two co-defendants, guilty on all counts. Harrelson was sentenced to two consecutive life terms in federal prison. His wife Joanne received a 25 year sentence, and Liz Chagra was handed a term of 30 years. Justice, it seemed, was being served.

The main event — the trial of the United States vs Jamiel Chagra — began in February 1983. This was an entirely different kind of contest. The defendant wasn't a cold-blooded killer, but a charismatic and popular crime boss. The venue was moved to Jacksonville, Florida, to escape the intense media saturation in Texas. And the defense table was anchored by the larger-than-life Las Vegas attorney, Oscar Goodman. This was the trial the Department of Justice had been building towards for years. This was their chance to prove that no one, no matter how rich or powerful, could get away with murdering a federal judge. But the prosecution, for all its confidence, faced a colossal challenge. Their case against Jimmy Chagra was a house of cards balanced on a single point: the testimony of Joe Chagra. Against Harrelson, Joe's testimony was supported by a mountain of corroborating evidence. But against Jimmy, there was no confession tape, there was no damning diary, there were no eyewitnesses who could tie Jimmy directly to the plot. The government's entire multi-million-dollar case rested on whether the jury would believe one brother's word against the other. And Jimmy Chagra's lawyer, Oscar Goodman, knew that was a weakness he could exploit.

Goodman's strategy was brilliant and audacious. He wouldn't just defend his client, he would effectively prosecute the government's star witness. The battle began with jury selection, where Goodman looked for individuals skeptical of government power — people who might believe that federal prosecutors would bend the rules to win a high-profile case. In his opening statement, he laid out the grand narrative he would sell to this jury. Jimmy Chagra, he argued, was not a kingpin, but a devoted family man — a loving husband and father who was being framed. And the man framing him, Goodman thundered, was his own weak, jealous, and treacherous younger brother, Joe.

While the prosecution's case was being dismantled, Goodman carefully managed his own client's image. Jimmy Chagra sat silently, dressed not in flashy Vegas attire, but in conservative suits. His wife Liz sat in the front row every day, the image of devotion. Goodman created a powerful courtroom tableau — the loving family on one side, and the lone, treacherous brother on the other, selling his story to the government.

The prosecution tried to fight back, to rehabilitate their witness, to remind the jury of the sheer logic of their case: that only Jimmy had the motive and the money to order the hit. But Goodman had successfully muddied the waters. He had transformed the trial from a referendum on Jimmy Chagra's guilt, into a referendum on Joe Chagra's character. In his closing speech, Goodman argued that the government was asking the jury to convict a man, and send him away for life, based on nothing more than the word of a single, compromised, admitted felon who had been given the deal of a lifetime.

"They have not met their burden," he declared. "They have not brought you proof beyond a reasonable doubt. They have only brought you Joe Chagra."

The jury deliberated for 13 hours. The prosecutors waited, hoping the jury would see through the defense's theatrical performance. Finally, the jury returned. The courtroom held its breath as the foreman handed the verdict to the clerk.

On the charge of conspiring to murder Judge John Howland Wood Jr: Not Guilty. On the charge of the murder itself: Not Guilty.

A gasp, then a wave of stunned murmurs, swept through the courtroom. Oscar Goodman put his arm around Jimmy Chagra. The government prosecutors sat frozen, their faces monuments of disbelief. Jimmy Chagra, the man who had set the entire, bloody, affair in motion, had walked. He was still convicted on the lesser charges of obstruction of justice and drug trafficking that would send him to prison. But on the main charge, the assassination of Maximum John, he was acquitted. It was a spectacular, humiliating defeat for the Department of Justice. The Not Guilty verdict on the murder charges echoed like a second gunshot through the halls of the Department of Justice. By the letter of the law, in the biggest trial of his life, Jimmy Chagra had won.

But the story of the assassination of Maximum John does not end with the bang of a gavel. The fallout from that single rifle shot in a San Antonio neighborhood would continue to ripple outwards for decades, a slow-motion shockwave of consequence that would ultimately consume everyone the conspiracy had touched. Justice, it turns out, is not always confined to a single verdict. Jimmy Chagra may have been acquitted of the murder, but he was still sentenced to a lengthy term in federal prison for his other convictions. And while behind bars, he proved that his capacity for violence had not been diminished by his trial. He was caught orchestrating another assassination plot, this time targeting the tenacious prosecutor who had faced him in court, Assistant United States Attorney James Kerr. The plot was foiled, but it was a chilling confirmation of Chagra's true character — a man who saw murder as a permanent solution to any problem.

It was this second conspiracy that ultimately led to the truth. Years later, with his appeals exhausted and his life reduced to a prison cell, Jimmy Chagra decided to make one last gamble. He entered into a formal deal with the federal government. In exchange for a possible reduction in sentence and, he hoped, the early release of his wife Liz, he finally confessed. He admitted, officially, to his role in both the successful murder of Judge John H Wood Jr, and the attempted murder of James Kerr. It was not a confession born of conscience, but a final, desperate bargain. And it was a bargain he would lose. The deal was meant to save the woman who had been his most loyal soldier, the Vegas showgirl who had delivered the suitcase full of blood money out of unwavering devotion. But Liz Chagra was never released. She remained in federal custody, and in 2005 she died of cancer, in a prison hospital in Fort Worth Texas. Her husband's confession had come too late to save her.

For Jimmy Chagra himself, the end was not a blaze of glory, but a slow, quiet fade into obscurity. He was eventually paroled in 2003. The man who once commanded a criminal empire and made casinos tremble, spent his final years living under the alias James Madrid. He didn't disappear into a comfortable life provided by witness protection, as was often rumoured — his sister would later state he was never in the program. Instead, he lived in a trailer camp in Mesa, Arizona, a ghost of his former self. In 2008, Jimmy Chagra died of cancer — a quiet, ignominious end for a man who had once burned so brightly.

The man he hired, Charles Harrelson, never saw a day of freedom. His life in prison was as audacious as his life on the outside — he was not an inmate who faded away. On July 4th, 1995, Harrelson and two other inmates at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary attempted a brazen escape. They fashioned a makeshift rope and were scaling a perimeter wall when a warning shot was fired from a prison tower. The trio surrendered, their desperate bid for freedom ending at the foot of the wall. Harrelson died of a heart attack in his cell at the Supermax prison in Colorado in 2007, at the age of 68, in the most secure prison in America. After his death, his sons, including the actor Woody Harrelson, inherited boxes of papers he had compiled, the raw material for a memoir he hoped would one day be published. In those pages, he finally admitted the truth of his life's work. He confessed to being involved in dozens of killings stretching back to the 1960s. His role, he claimed, was often as a driver or planner, but he admitted to being the primary assassin in at least six murders. His reputation was not a myth, it was an understatement.

And the collateral damage continued to spread. Joe Chagra — the lawyer brother caught between family loyalty and the law — served six and a half years of his ten-year sentence. After his release, a man stripped of his profession and his family's trust, he tried to build a new life. But in December 1996, at the age of 50, he died from injuries sustained in an automobile accident. A sudden, tragic end for the man who served as the linchpin of the entire conspiracy.

In the end, no one escaped. The hitman died in the nation's most secure prison. The mastermind died in a trailer park. The loyal wife died in a prison hospital. The lawyer brother died on a highway. A courtroom may have delivered an imperfect verdict, but karma, perhaps, was more patient, and its aim was true.

The assassination of Maximum John was a wound on the American justice system, a moment of profound crisis. But it led to lasting change. The U.S. Marshals Service created its Judicial Security Division in direct response, an agency dedicated to protecting federal judges from the very threat the Chagra conspiracy had made real.

The crime stands as a dark, sprawling Texas epic — a reminder that the single, sharp crack of a rifle on a quiet morning can set off a chain reaction of ruin that takes decades to finally settle, leaving a legacy of tragedy. And a complex lesson about the true, inescapable, cost of crime.

More Episodes

The Ann Arbor Hospital Murders

In the summer of 1975, panic swept through an Ann Arbor hospital. Patients in the intensive care unit, many recovering well, inexplicably stopped breathing. Doctors and investigators raced to find the cause, realizing this was no medical anomaly — it was murder. Read more

The Vanishing of John Ruffo

In 1998, John Ruffo, a charismatic New York businessman, was due to begin a 17-year sentence for an audacious $350 million bank fraud. He drove to an ATM, withdrew a few hundred dollars, abandoned his car at JFK airport, and simply vanished. Read more